By Corinne H. Smith

“The greatest compliment that was ever paid me was when one asked what I thought, and attended to my answer. I am surprised, as well as delighted, when this happens, it is such a rare use he would make of me.” ~ Thoreau, “Life Without Principle.”

In my work at a used bookstore, I happen upon references to Henry Thoreau on a semi-regular basis, often without warning. Last week he showed up three times. And in each instance, someone offered a unique interpretation of his words.

The first came in a 1927 book called “Handmade Rugs” by Ella Shannon Bowles (1886-1975). Bowles was the author of a number of craft-related books in the early 20th century, including “Practical Parties,” “About Antiques,” and “Homespun Handicrafts.” Later she wrote several books based on geography and New Hampshire. How did she somehow bring Thoreau into her narrative about home-made rugs? Amazingly enough, in the final and concluding paragraph, where she wanted to emphasize how much of themselves the rug-makers put into their work:

Thoreau says the value of a thing is determined by the amount of life that goes into it. So home rug-making will live on, as far as the craftswoman expresses herself in the products of the rug hook, the needle, and the loom.

While this is a nice sentiment, I don’t believe it’s quite what Thoreau had in mind. The sentence Bowles was referring to was from the “Economy” chapter of Walden: “The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” Bowles had remembered the idea from the point of view of the creator, and not of the purchaser, as Thoreau had. These are slightly different takes, and both equally valid. But hardly the same. We also have to wonder how Bowles knew of and read Thoreau, since his circle of fame was still rather small in the 1920s. Perhaps being based in New England helped her.

The second time Thoreau came to me was in the fifth edition of “Much Loved Books: Best Sellers of the Ages,” by journalist and literary critic James O’Donnell Bennett (1870-1940). It too originated in 1927, with a 1932 library edition. It was a collection of 60 lengthy columns that Bennett wrote for The Chicago Daily Tribune. Here he extolled the virtues of select classics, including Walden. He practically tripped over his enthusiasm for Thoreau and his work:

Of Thoreau’s masterpiece two wonderful things are true –

No man having attentively read it is ever the same man again,

Second – Nobody ever wrote a book in our tongue like it.

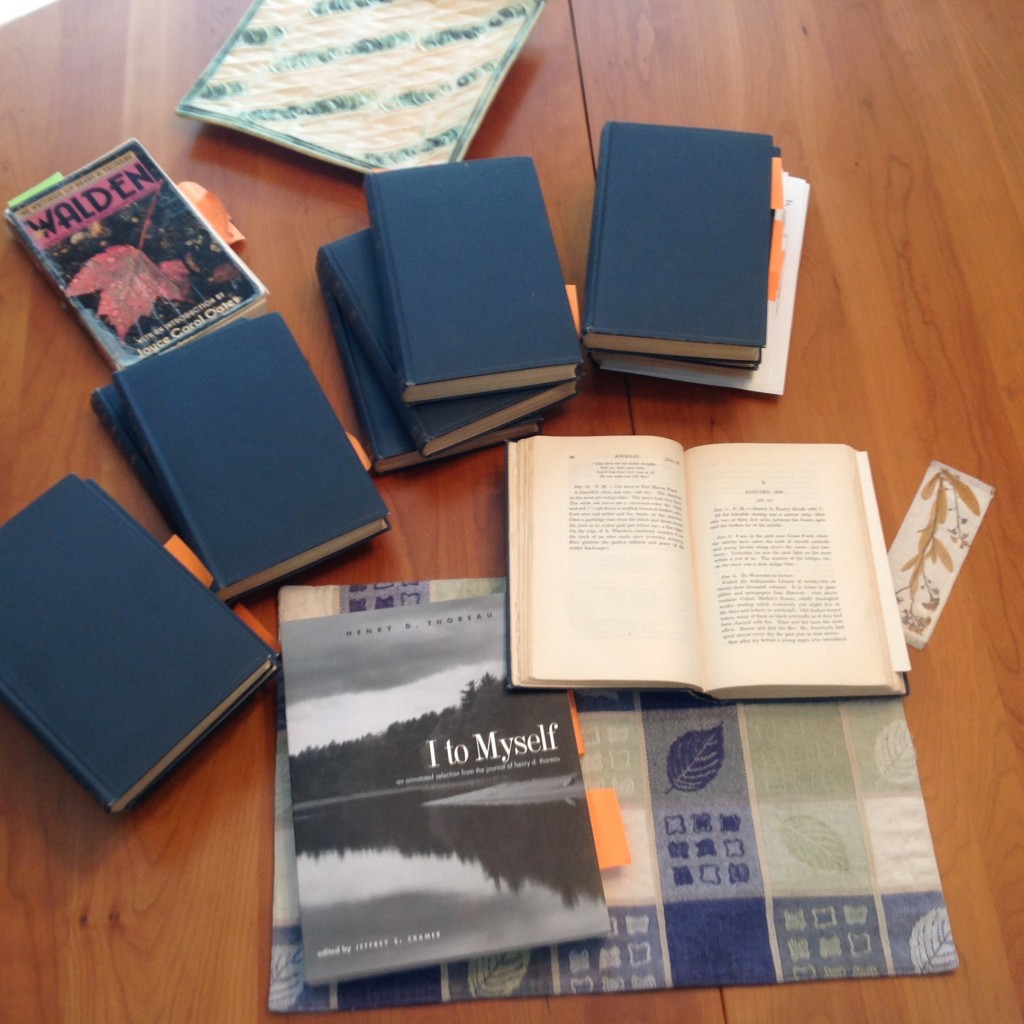

And this was just the beginning. Bennett gushed over Thoreau and Walden for nine pages. He mentioned that he had visited the Concord Antiquarian Society, the predecessor to the Concord Museum. And he was quite familiar with the 20-volume set of Thoreau’s works that was published by Houghton, Mifflin in 1906, as well as Ellery Channing’s biography, Thoreau: The Poet-Naturalist. I don’t believe I’ve read a more devoted tribute from someone from this time period. His concluding paragraph read:

He is the bonniest, gravest, honestest spirit in our literature, and his great book has the sunshine, the crisp snow, the bird notes, the morning light and the morning fragrance of Walden pond bound in with every one of its nearly 400 steadying, exhilarating, comforting pages. It lives and sings.

Wow! When Bennett died, he left his library of 7,000 volumes to The Tribune for use by the journalists. His funeral announcement in the paper said: “He liked to read random bits from such writers as Thoreau, Hazlitt, Tolstoy, Emerson, Hawthorne, and Shakespeare, his personal literary gods.” Bennett sure had a good core group at his fingertips.

The final time Thoreau showed up at the bookstore last week, it was in conversation with a regular customer, whom I’ll call Earl. Earl is in his late 70s, and he likes to talk. When he brought three big, colorful books on European castles to the checkout desk, he told me he was saving up his money to make the trip across the ocean to see some of these castles. We chatted about travel and books and other random subjects. Earl is the kind of person who has been places and has read widely, and this was not the first time he and I had talked.

Somehow my interest in Henry Thoreau came out. Earl seemed pleasantly surprised at this news, probably because it turned the conversation in a different direction. He admitted to me that he had once read the book that he mistakenly called “On Walden Pond.” (See my earlier post about this phenomenon at https://thoreaufarm.org/2013/10/two-ponds-or-two-henrys-one-work/.) I chose not to correct him.

“Do you know what my favorite part was?” he asked.

I shook my head. With Earl, it could have been anything.

“My favorite part was when he said that you should dig deep. I liked that. I think this is what I’m doing with my castle research and with the other historical subjects I’m interested in. I’m really digging into them, and I’m enjoying it very much.”

I commended him on his research and his choices. At the same time, I marveled at the fact that out of the entire text of Walden, the one sentence that resounded most with Earl was: “I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” Yet I had no doubt that this was exactly what Earl was doing.

Here were three different voices from three different sources and with three different interpretations. You never know what piece of Thoreau’s work people will take and what perspective they will have on it. I continue to be amazed at how far he continues to reach.