by Richard Higgins

Few will forget that last year at this time New York told us that Henry Thoreau was really a cheerless curmudgeon and hypocritical scold with the heart of Ted Kaczynski and the writing ability of Bronson Alcott. Many were astonished that the Thoreau Society had somehow missed this for this 75 years.

Now from New York comes another October surprise, this one from the Times, not the New Yorker. Also overlooked by Thoreau and Concord partisans, it recently announced, is the fact that the pencil capital of 19th- century America was–drum roll, please –New York City! Who (beside Kathryn Schulz) woulda thunk it?

I will not play fast and loose with the facts (unlike some writers), so I will corroborate. On Tuesday, October 11, 2016, a metro column in The New York Times began:

New York Today: Our Past in Pencils

BY ALEXANDRA S. LEVINE“With school back in full swing (except for all the days off recently), let’s sharpen our knowledge of New York history.

Today’s lesson: How our city was once the capital of pencil manufacturing in the United States.

It further stated that New York in 1861 had, and I quote, “one of the country’s first lead-pencil factories.”

Now, are we who are in the know going to savage the author of this ridiculous claim with vicious personal attacks? Of course not. Concord people are decent and forgiving. Ms. Levine is probably a sincere and lovely person in addition to being a criminally inept reporter.

As everyone else knows, Concord had sophisticated and productive pencil factories while raw sewage still flowed on New York streets and no one dared venture into the raving wilderness above Wall Street.

Here, Ms. Levine, not to put too fine a point on it, are the facts:

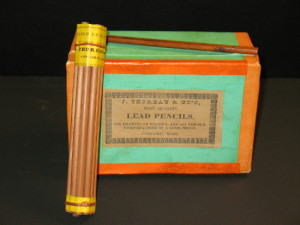

The first wood pencils in the New World were made in Concord in 1812 when William Munroe invented a machine to cut and groove wood slats and filled them with a graphite paste. Fifty-nine (59) years later, in 1861, Eberhard Faber built what the Times calls the first “large-scale” pencil-making factory, in New York. Munroe’s shop was primitive by comparison. However he produced 175,000 pencils in 1814, only two years after starting, and five million pencils in 1835 alone. Sounds large-scale to me.

Munroe was soon joined by a cluster of prominent pencil makers in Concord and surrounding towns, including Ebenezer Wood (Acton), Joseph Dixon (Salem), Benjamin Ball (Harvard) and, most famously, in 1821, the father of the humorless misanthrope, and then the insufferable sourpuss himself. It was partly because of Henry Thoreau’s involvement that Concord led the pencil industry in the United States into the 1840s. At that time, Thoreau pencils were among the most sought after in the country.

Concord pencils apparently were even admired in New York. In a family history, Munroe’s son wrote that some of his father’s less principled competitors illegally slapped Munroe labels on their stock. “One merchant in New York”—that putative pinnacle of all things pencil—“sold German-made pencils with ‘W. Munroe’ on them as illegal knock-offs.” No names mentioned, but just noting that Eberhard was from Bavaria.

The question then is: What makes one pencil-producing city the pencil capital of a nation? The quantity of cheap pencils turned out? Probably not. Would not innovation and quality be better criteria?

If so, honors must go to 01742. Here’s why:

Concord pencil makers early on mixed graphite with wax, spermaceti and other substances. All worked but had drawbacks. The French were the only ones who knew the right recipe. Nicolas-Jacques Conté invented the modern pencil lead in 1795 by mixing graphite with clay—but he kept the formula a strict secret. Henry Thoreau decided to find the perfect graphite mix on his own. After researching it at the Harvard Library in 1840, he hit upon the idea of using clay—rediscovering what the Frenchman had figured out 45 years earlier. The result was a pencil lead that was harder and darker than any his family had made.

Thoreau also designed a machine to grind graphite better and another one to drill a hole lengthwise through the wood slats so the lead could be slid inside. The only reason the Thoreau family got out of the business was that the right recipe soon became common knowledge, resulting in stiff competition. The Thoreau’s wisely abandoned the pencil business in 1853 for a more profitable one: selling powdered graphite (“plumbago”) for use in electrotyping.

Having now settled this matter, to be fair I should point out that when I gently informed Ms. Levine by email of her error, she was the soul of grace. She apologized and promised a correction. I thanked her and said having at least one of these October misrepresentations corrected would set many local minds at ease. Her reply was not encouraging. She was off to her next story. New York workers, she said, have found the exact spot where the original Concord grape grew in Central Park.

Writer and editor Richard Higgins lives in Concord. University of California Press will publish his Thoreau and the Language of Trees in March 2017. He may be reached at rihiggins@comcast.net.

‘