By Corinne H. Smith

Here’s another Thoreau-related story from my day job at the bookstore. This time I got my hands dirty.

The boss gave me a stack of boxes to go through. My job was to figure out what was in them and to catalogue the volumes into our database. “There might even be some Thoreau in there,” he said. He knew what to say to get my attention.

I lifted the lids and saw that each box contained bound volumes of old magazines. VERY old magazines. Most were from the 1800s, and I had never heard of them. He was right. There could be some Thoreau in here. We were certainly dealing with the right time period.

What fun it was, to handle and read some of these 19th-century issues! They were intended to bring enlightenment and entertainment to people living away from the east coast cities. Here was “The Cultivator: A Monthly Publication to improve the soil and the mind,” with its great mission and tagline. Next was “The Rover: A Weekly Magazine of Tales, Poetry, Legends, Wit, Romance & Art.” I guess it wanted to cover every base. “The Rural Repository” had an even higher goal. It was “Devoted to Polite Literature, such as moral and sentimental tales, biography, traveling sketches, notices of new publications, poetry, amusing miscellany, humorous and historical anecdotes, &c. &c.” Some of these periodicals included engravings of real or fictional scenes. I love this stuff.

I was especially eager to pick up and look through the three volumes of “The Daguerreotype.” Henry Thoreau famously sat for a daguerreotype session with Benjamin Maxham in Worcester in June 1856. I knew it had been merely a short-term career for Maxham, and that he left Worcester a few years later. Maybe I could learn more about him here. But no. The magazine only spanned the years 1847-1849, and it only copied articles from France, England, and Germany. And it had no illustrations at all. None! What a letdown.

I put aside the heaviest and the messiest but matching books for last. Almost all of these volumes had crumbling outer spines. A reddish-brown dust poofed away from the books and onto my hands. In many instances, both the front and back covers had separated from the spines. Some were tied with a black ribbon to stay together. Each book was about two inches thick. They were old, they were in bad shape, and they were substantial. But amazingly enough, the bindings were the only awful part. The pages they were protecting were quite clean and readable. They were almost as pristine as the days they were printed.

This set turned out to be the first 23 volumes of a periodical called “Southern Literary Messenger.” It was published in Richmond, Virginia, from August 1834 until June 1864, when the war intruded enough to stop it. Our run went from 1834-1856. This was a major publication, and it contained literature and reviews of work from both Northern and Southern authors.

Edgar Allan Poe contributed a number of essays, poems, and reviews to the “Messenger” in its opening years, and he even served as editor for a bit. I found “The Raven” in volume eleven, 1845. It wasn’t the poem’s first publication, but it was still an early one. I also read his review of James Russell Lowell’s “A Fable for Critics.” Poe didn’t mention how Lowell chastised Thoreau for resembling Emerson; but he did manage to diss both Lowell and Margaret Fuller simultaneously. (You can read a transcription of his critique at http://www.eapoe.org/works/criticsm/slm49l01.htm.)

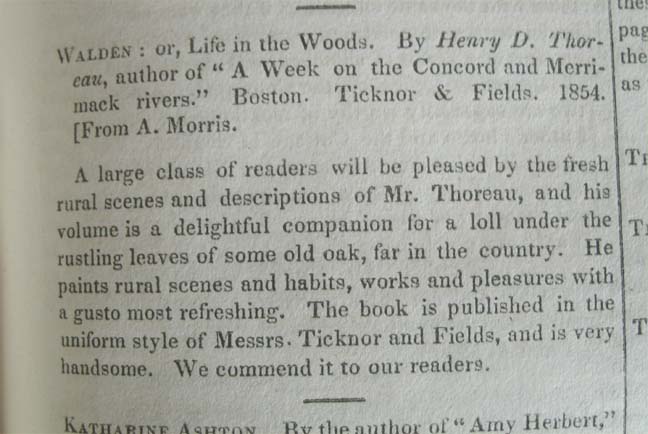

What could I find related to Thoreau here? Well, “Walden” came out in August 1854. Maybe there was a review …. And yes, wouldn’t you know it? In the September 1854 issue, I found a combination announcement and review of Thoreau’s second book.

I wonder how many Richmond residents ran down to the store of bookseller and publisher Adolphus Morris after reading this paragraph? How well did Henry’s words sell in the South, back then?

Alas, while this was a new-to-me find, it was not a new one to the realm of Thoreauviana. The text of this review appeared in The Thoreau Society Bulletin in 1954. And yet, it’s still fun to launch such treasure hunts when wading through drifts of 19th-century pages.