By Corinne H. Smith

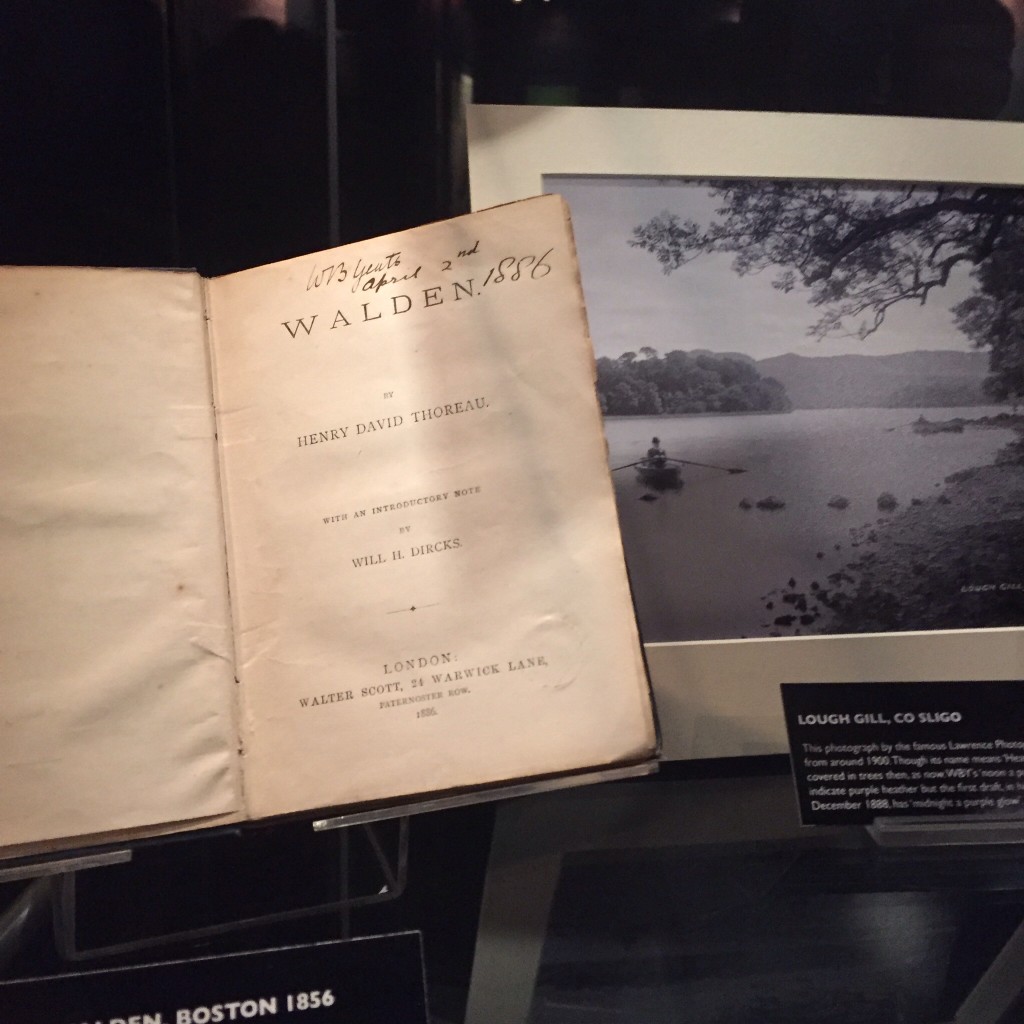

“The mice which haunted my house were not the common ones, which are said to have been introduced into the country, but a wild native kind not found in the village. I sent one to a distinguished naturalist, and it interested him much. When I was building, one of these had its nest underneath the house, and before I had laid the second floor, and swept out the shavings, would come out regularly at lunch time and pick up the crumbs at my feet. It probably had never seen a man before; and it soon became quite familiar, and would run over my shoes and up my clothes. It could readily ascend the sides of the room by short impulses, like a squirrel, which it resembled in its motions. At length, as I leaned with my elbow on the bench one day, it ran up my clothes, and along my sleeve, and round and round the paper which held my dinner, while I kept the latter close, and dodged and played at bo-peep with it; and when at least I held still a piece of cheese between my thumb and finger, it came and nibbled it, sitting in my hand, and afterward cleaned its face and paws, like a fly, and walked away.” ~ “Brute Neighbors,” WALDEN

This week I partnered on a Thoreau-related project with a young fifth-grader named Henry. We met at Thoreau Farm and set up our stuff in the first floor parlor. For one part of our project, I needed some water. So I walked into the tiny kitchenette, found a glass in a cabinet, filled it with water, and took it into the parlor.

After we finished our project, I took the glass back to the kitchen. I dumped the water down the drain, rinsed the glass a bit, and left it in the sink. I hadn’t noticed anything else in the sink when I had first filled the glass. But now I thought I saw something small and dark in there. Perhaps, with a tail. I turned on the overhead light to look again. Sure enough, it was a tiny mouse. It was cowering against the stainless steel side. Had I accidentally dumped water on it? I hoped not. I spoke quietly to it and apologized. Then I went back to find Henry.

“I found something in the kitchen sink, Henry,” I said. “A live mouse.” His eyes got big. “Want to see it?” I asked. He nodded.

We walked into the kitchenette, and he peeked over the edge. “Oh, wow!” He hurried back to the parlor to tell his mother what he had seen. She was not a fan of mice. She shivered and stayed right where she was standing.

“I want to rescue and relocate it,” I said. “Will you help me, Henry?” He agreed. We walked back. I noticed that Henry kept his distance, though. He stayed away from the counter and let me, the grown-up, manage the task at hand. I had decided that putting the mouse outside was an unacceptable solution. Where else could I move it, away from the kitchen? The basement.

I grabbed a paper towel. “Okay, I’m going to grab it somehow, and we’re going to take it down to the basement,” I said. I looked at the mouse, who was still cowering. I didn’t know where it had come from or where its nest was. Naturally, there were spots along the edgework that didn’t quite meet the walls. Maybe the mouse lived under the cabinets. Maybe it had run across the counter in search of crumbs, slipped into the sink, and couldn’t find a toehold on the silvery walls. It had been temporarily trapped. Well, the basement should make a fine home for it, too. “I’m going to pick it up somehow,” I said again.

“Maybe you can put it in the glass to move it,” Henry suggested.

“Good idea. Except that I don’t really want to use that drinking glass. I wonder if we have any paper cups.” I opened a lower door and spied a few. I loosened one from the others. I put it into the sink and pushed the mouse into it with the paper towel. I covered the opening so it couldn’t get out.

“Its tail is sticking out of the cup.”

“That’s okay. Let’s go.” Henry fairly ran to the basement door, turned on the lights, and led the way down the steps. I followed, carrying the covered cup.

“Now. Where should I put it?” The basement is semi-finished. The limestone rocks of the foundation jut out from every side. I guessed it didn’t matter where I put the mouse. It would figure out the best place to go, on its own. So I laid the cup on its side near a central wall. I took the paper towel away and peeked inside. Now it was the mouse who had the big eyes, looking right at me. I wished it well. Henry and I backed up. We watched the cup rock back and forth slightly, as the mouse moved around inside. It would be okay. We didn’t wait for its re-appearance. We trudged back up the steps. Our work for the day was finished, all around.

Well, Mr. Thoreau, we didn’t go the extra mile that you did. We didn’t deliberately feed this mouse and let it run all over our clothes. I guess I did kind of play peek-a-boo with it, though. And we saved it for you and put it in the basement. Now we can confirm that one of your houses is once again enlivened by mice.