A favorite poem for the month, for spring, for the day-by-day

During his years as U.S. Poet Laureate, Robert Pinsky set up one of my favorite initiatives – The Favorite Poem Project. In community readings and audio files and online readings citizens were asked to choose and recite or read aloud a favorite poem, one that stayed with them, whispered encouragement, or understanding, or solace…whatever the times. For a while poems appeared spontaneously, sometimes in odd places, unexpected against the daily din, or amid the billboards of announcement.

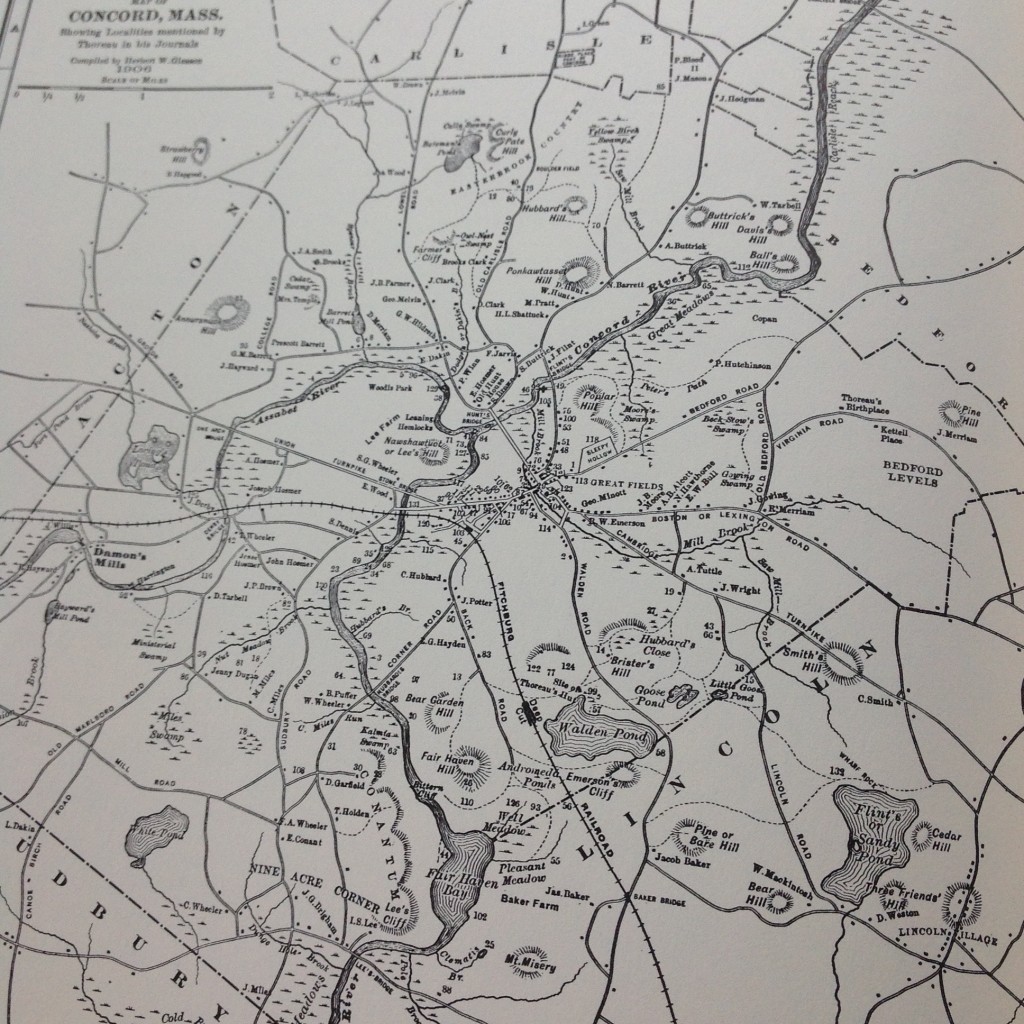

Though I never committed it to tape or YouTube, I carried with me a favorite poem, a sort of poem in your pocket, or, in my case, poem in your wallet. And I read this poem often, as reminder, as map to the day really. Here, with a thought or two to follow, and then a request, it is:

Mary Oliver’s Going to Walden

It isn’t very far as highways lie.

I might be back by nightfall, having seen

The rough pines, and the stones, and the clear water.

Friends argue that I might be wiser for it.

They do not hear that far-off Yankee whisper:

How dull we grow from hurrying here and there!

Many have gone, and think me half a fool

To miss a day away in the cool country.

Maybe. But in a book I read and cherish,

Going to Walden is not so easy a thing

As a green visit. It is the slow and difficult

Trick of living, and finding it where you are.

Once, while waiting for a speech to begin, I talked with Oliver about this poem, and she pointed out a feature I hadn’t noticed before – the two stanzas appear like tablets, stone on which is written a meditation on life and a route to it. The stanzas are stolid in appearance, even as their language is not; they will endure, as stone does. A reader, this reader, may return to them, even as s/he engages in “the slow and difficult/Trick of living, and finding it where you are.”

I am glad to return to this favorite poem as spring appears, hesitates, vanishes, reappears. Spring too is on more than a “green visit”; perhaps the going is “slow and difficult,” but I hope you are “finding it where you are.”

Send on yours, if you wish.

A few links to the Favorite Poem Project: