By Corinne H. Smith

Thoreau Farm and The Thoreau Society recently held their annual online fundraising auction. Coincidentally, news of a long-ago auction with Thoreau ties came my way at the same time.

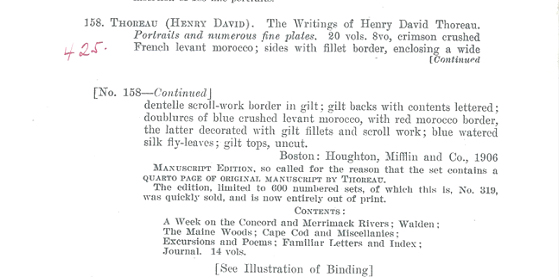

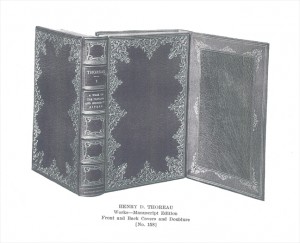

In my job at a used bookstore, I handled an auction catalogue from April 14, 1920. It was a nondescript tan paperback that was missing its cover. The title page described the auction collection as “The Complete Writings of Distinguished American, English and French Authors in Finely Bound Library Editions: The Magnificent Library of Colonel Jacob Ruppert of New York City.” As I turned a few pages, I saw 175 listings of classic books and large book sets by many famous authors: Dickens, Shakespeare, and Trollope, to name just a few. Some entries included staged photographs that showed off the leather bindings, lavish gilt decorations on the covers and the inside flyleaves. This did indeed look like a magnificent library, and one where the books had hardly been handled. They may never have been read.

I was intrigued. Who was Jacob Ruppert, and how had he amassed this collection? After searching for more information, I learned that he was probably the American businessman and National Guard colonel who was also the owner of the New York Yankees from 1915 until his death in 1939. Ruppert therefore had the money to buy such fine volumes. Why had he decided to auction them off in 1920? This was a question left unanswered. Maybe he was merely downsizing to gain some ready cash.

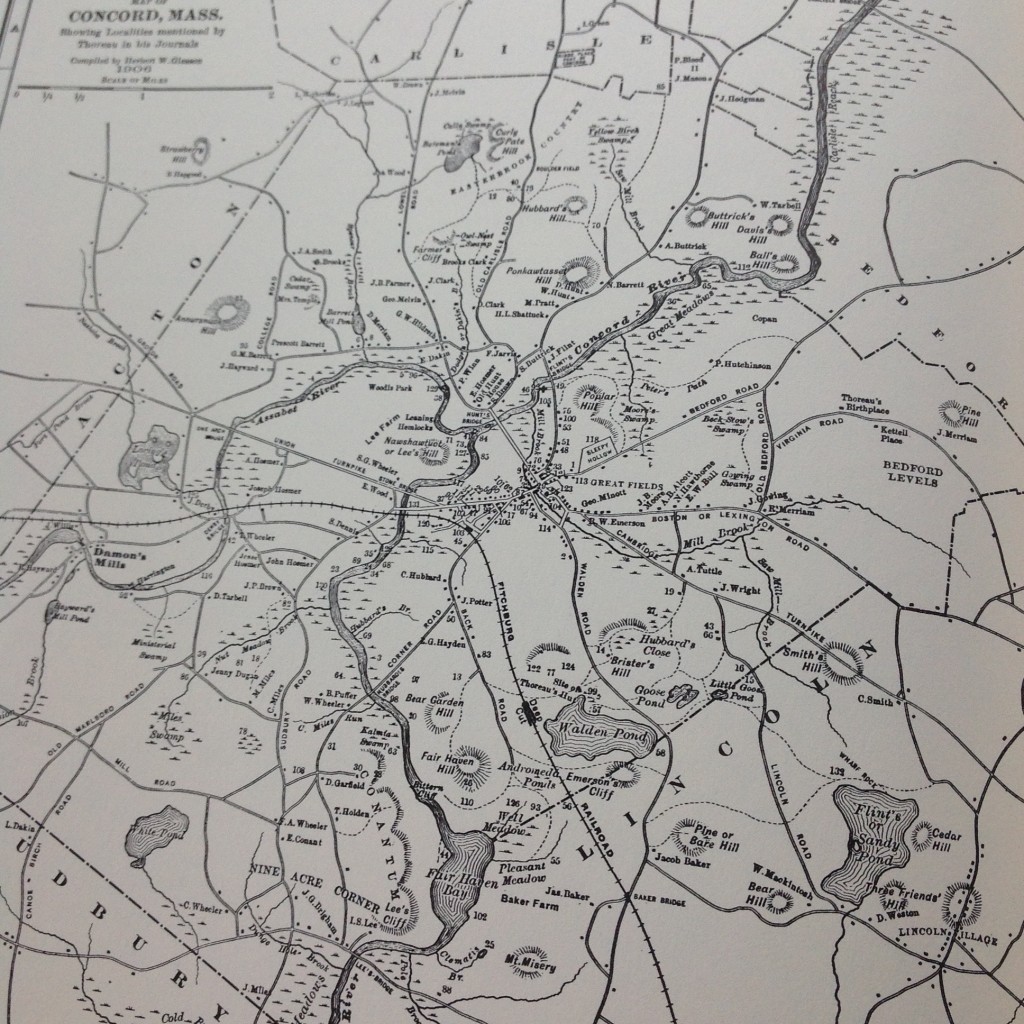

The lots were listed in alphabetical order by author name. Automatically I turned to the Ts and looked for Thoreau. Bingo! Ruppert had owned a manuscript edition copy of “The Writings of Henry David Thoreau,” the 20-volume set published by Houghton Mifflin and Company in 1906. This meant that an original piece of handwritten manuscript was also included. Only 600 of these numbered manuscript sets were released. Ruppert’s was #319.

The person who had once owned this catalogue must have gone to the auction. He or she wrote the winning bid prices in the margins. This Thoreau set sold for $425. My next questions were: Who had bought it? And where was it now?

I contacted Elizabeth Witherell, editor-in-chief of the Princeton editions project that continues to update the Writings volumes. Beth is based at the University of California, Santa Barbara. I figured if anyone had a list of the whereabouts of the 600 manuscript editions, she would. She did. And her most current list contained no entry for #319. The Ruppert auction item was new information.

The manuscript edition list that Beth sent me included details of the libraries, private collectors, and booksellers who have been known to own these special copies of the 1906 set. It even quoted the text from the original manuscript pages, when it was known. It included details of archives where some of the handwritten pages are now found. Sadly, some have been lost or destroyed. One of Beth’s questions for me was if the Ruppert auction catalogue described exactly which Thoreau manuscript page accompanied the set. I had to tell her that unfortunately, it did not. This remains another mystery.

I sent messages to a few other special libraries that own copies of Ruppert’s 1920 auction catalogue. None of them had further annotations or details on who bought the items at the sale. All we know is that the new owner paid $425. The books could be anywhere now.

Several sets of the 1906 Writings manuscript edition are on the market today. Asking prices range from $12,000 to $19,000. More than a century after their publication, we have to wonder: What would Jacob Ruppert think? And, what would Henry Thoreau think?

[If you own one of the manuscript sets or know the location of one, and you would like to make sure it is informally registered on the master list, please e-mail Corinne at corinnehsmith@gmail.com.]