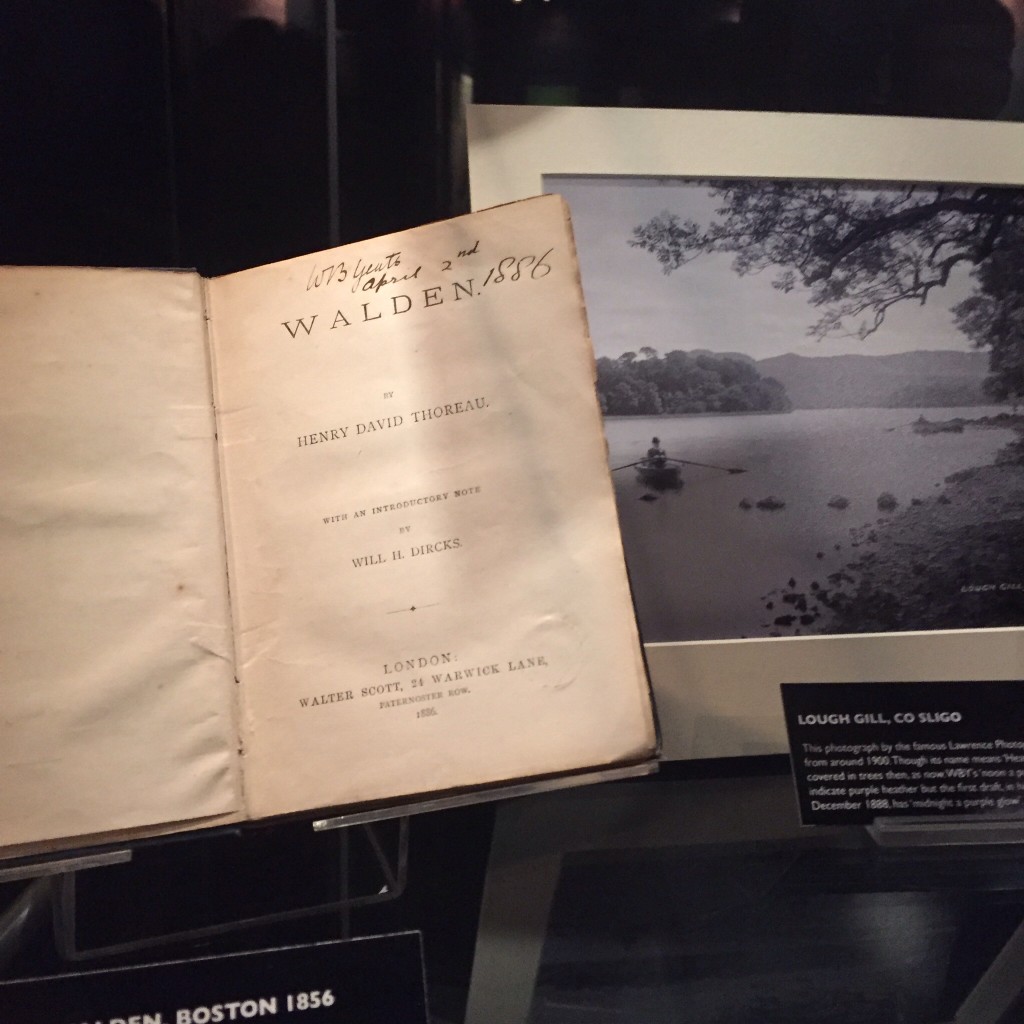

“Every man, I think, reads one book in his life, and this one is mine,” E.B. White wrote of “Walden” in a 1953 New Yorker piece. “It is not the best book I ever encountered, perhaps, but it is for me the handiest.”

The other day a Google alert that feeds me regular notice of Thoreau’s appearance in media across the web, offered me a link to a reflective piece that had just appeared on Salon.com. Benjamin Naddaff-Hafrey’s pleasureable essay opened at the end of E.B. White’s life and then rolled back through his long attachment to Walden and the many copies White owned, read and gave away, including a 1964 edition (complete with a rain-shedding duraflex cover) to which he wrote the introduction.

The traced arc of White’s connection to Walden made me look back over my own, a mostly pleasant stroll through seasons of learning and teaching, and that, in turn, brought on reflections from over three years of writing for The Roost. How many books and writers could both sustain my interest and provide so many points of thinking and writing departure? Answer: one.

If one accepts White’s proposal, the question follows: how do you know when you’ve picked up and read your life-book? For me the answer arrived slowly. My first reading of Walden was hardly a reading at all. Assigned the book in a high school English class, I turned dutifully to it on evening one and fell promptly asleep. The pattern continued through the three weeks we considered sections of the book, and there was also an alarming transference to class time, where my chronic head-bobbing intensified, lowering my teacher’s already low estimation of me. I missed entirely Thoreau’s discontent with the sort of schooling I was sleeping through, and I missed his affection for the outdoor world where I felt truly animated. I did benefit from the cautionary message of this sleepy passage years later when I began to teach Walden, but my first meeting with Henry Thoreau was akin to passing someone of the street.

Jump to college and a reading with a touch more adhesive. I got – mostly by listening to lectures – some of Thoreau’s central critique of his (and, by extension, my) world, and I noted that the place he went for insight and wisdom was like mine, wooded and hilly. All good, but not exactly a scrivmance.

Then there was the long, oblique approach to my life’s work, teaching. By the time I landed in an English Department some 20 years along, I knew quite a bit about teaching and writing and a lot about being outside, but I’d not returned to Walden, though as a journal editor, I’d received any number of pieces to which it was important. Then, a year or two into my English career, my department chair said, “So here we are in Concord, and, since Phil retired, no one’s been teaching Walden. You spend too much time in the woods. How about you?”

Of such questions long affection is born. I arrived at my life-book late, much later, for instance than White did, but, after 25 years of readings, teachings, and any number of epiphanies, major and minor, I’m still turning its pages, still awake to its possibilities. I keep Walden handy.