By Corinne H. Smith

I last led a nature writing walk to Two-Boulder Hill at the end of March. Back then, we had to walk around a few patches of ice, but we still had a terrific time. (See https://thoreaufarm.org/2014/04/a-visit-to-two-boulder-hill/ for the whole story.)

What a difference three and a half months can make! During The Thoreau Society’s Annual Gathering in mid-July, three of us took the same walk. Well, it can never be the SAME walk. We followed the same general path, and we witnessed the sights and sounds of Summer this time.

Charles and Lucy and I met at Thoreau Farm and began walking north. After we passed the Gaining Grounds fields and the woods behind them, we reached a little-used access road. Here we caught sight of flowers that like to live in these kinds of disturbed areas: the yellow bird’s foot trefoil, yarrow, tiny Deptford pinks, and Queen Anne’s lace. We watched as the smallest butterfly we’d ever seen lighted upon a small dark log. Upon further inspection, we thought that its perch may have been coyote scat. We had indeed approached Wildness pretty quickly.

On this steamy July day, with no clouds in the sky, the sunlight was too strong for us to stand in one place for very long. We walked along the trail and looked around for a shady spot to sit. We ended up just plopping down in the middle of the path, only an arm’s length away from one another. But we all had writing experience, and we quickly got ourselves into the proper frames of mind. We watched, we listened, and we quietly wrote in our journals.

We were surrounded by a dense forest that the wind brought to life. Breezes fluttered through all of the trees and branches above us. Lucy noted later that it sounded as if we were sitting at the edge of a big green ocean, with waves of leaves cooling us off instead of water drops.

After about fifteen minutes, I caught a hint of familiar flute-like tones. No! Was it possible? Had we been discovered by Henry David Thoreau’s favorite bird, the wood thrush?

I waited a few seconds, and the call came again. I was sitting a little closer to Charles, and I whispered to him, “I don’t believe it.” He cocked his ears and listened, and we heard the song again. Charles understood and nodded. He lifted his binoculars to see if he could see the bird. We alerted Lucy, too. Somewhere in the overgrown thicket in front of us, a wood thrush sang its beautiful tidbit song.

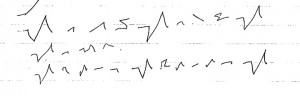

Thoreau called the wood thrush “the finest songster of the grove.” He wrote glowingly of the bird and its music. His journal entry for July 5, 1852, puts the thrush on an especially high pedestal, for the length of a full long paragraph. “Whenever a man hears it, he is young, and Nature is in her spring,” he said. It was true. The temperature suddenly became more tolerable for us. We listened as the bird came and went: always out of sight, but always sharing its music. I scribbled a rough transcription of the thrush’s jagged but magical melody line:

(You can hear the typical wood thrush song on Cornell’s All About Birds web site at http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/wood_thrush/id.)

Eventually I glanced at my watch. It was time to start walking back. I told my companions that we had to leave. Charles looked at me and said, “I could stay here all day.” Lucy and I felt the same way. Now THAT’s the sign of a worthwhile nature-watching and writing outing. Reluctantly we got up, brushed ourselves off, stretched our legs, and sauntered back to Thoreau Farm.

Charles was inspired to write a poem about our forest visitor.

Wood Thrush

Sitting in woods listening for sounds —

airplanes the winds shifting in the trees

cicada catbird then the faint

silvery voice, “come to me” “come to me”

the winds blow hard tossing treetops

we wait longer then the bird is nigh

“come to me!” yet closer “come to me!!”

I aim binoculars cannot see him

then silence — only the wind remains

this shy liquid-voiced singer

is the soul of the listening forest

~ Charles T. Phillips

This was indeed a day that the three of us will remember. And all we really did was take a walk in the woods.