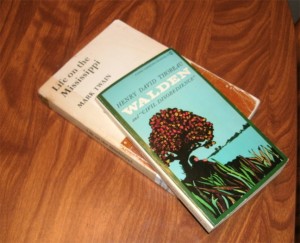

“When he has obtained those things that are necessary to life, there is another alternative than to obtain the superfluities; and that is to adventure on life now, his vacation from humbler toil having commenced.” “Economy,” Walden

Scene from a few days ago: The short-long month dwindles to a day, even as the morning temperature (ten below zero) offers reminder of its power. I’ve just returned from some days in the White Mountains, where, true to their name, winter’s grip endures. Each day, I climbed out of night’s valley toward the ridge-tops, feeling the cold sharpen as I got higher, and heeding its insistent reminder that winter climbing is all about carefully managing temperature, a lesson in essential heat that Thoreau considers at the outset of Walden.

Walking up on snowshoes also gives you ample time to think- it is the slowest form of walking I know – and I spent some of that time considering my little island of heat on the way up. The counterintuitive trick in deep cold is to avoid overheating and its bath of sweat, which, if generated, tends quickly toward ice when you stop and cool. As all winter walkers know, this focus leads to a parsing of layers of clothing that is different for each walker. I spent considerable steps debating 3 versus 4 layers, adding in consideration of a tucked versus an untucked underlayer.

Then, there was our adaptability to cold to figure – in short the longer your exposure to cold, the more you acclimate to it. Even my three days of climbing pointed this out. By day three, I was down a layer, even as the temperature stayed stubbornly near zero. And, as further example, I recalled a few years ago being out on Zealand Mountain on a zero-degree day, when the caretaker for the nearby hut passed us wearing only shorts and a halter top as she cruised up the trail. Yes, she did admit to “layering up” once she reached the open ledges near 4000 feet, but her winter of living in an unheated hut had given her impressive resistance to cold.

Finally, there was the feeding of my “firebox,” a practice nearly identical to that of keeping a wood stove going throughout the day. (Thoreau notes this analogy as well.) I learned stoves during a winter in a wood-heated cabin when I was in my early 20s. By March, I could mix woods of varying density and dryness to get the consistent heat of a slow burn day and night. And, having become inured to the cold, I kept the cabin at around 50 degrees. So too with the burn of the body’s fuel during winter walking – mixed feedings, often while still walking, keep you warmer. And here is happiness: enduring cold asks for calories of fat. You like cream cheese or butter? Bring (or layer) it on. It’s not unusual for someone out in deep cold to burn 5000 calories in a day. Falling short of that intake can bring on insistent chill.

I know too Henry Thoreau set out on snowshoes when winter was deep – I saw his snowshoes at last year’s exhibit of Thoreauvia at the Concord Museum – and surely he left a record of sensitivity to temperature – both his and that of the Walden world. Thoreau understood that we are truly thermal beings; sometimes it takes winter drive home our dependence.

Postscript: for 24 hours after returning from days outdoors in the cold mountains, I got thermal reminder: indoors, even with central heating set low, I burned with heat. Then, the fat worked through my firebox, and I returned to the temperate feedings and feelings of the lowlands.