Even when I take some days away from reading Thoreau’s journals, as I have recently, he finds his way into my day.

For some reason February always contains time unaimed, and in it, I lose the linear resolve of reading. In books, line follows line, but in my mind ellipses take words’ places, and whole paragraphs go by in some sort of wooly time. I try again.

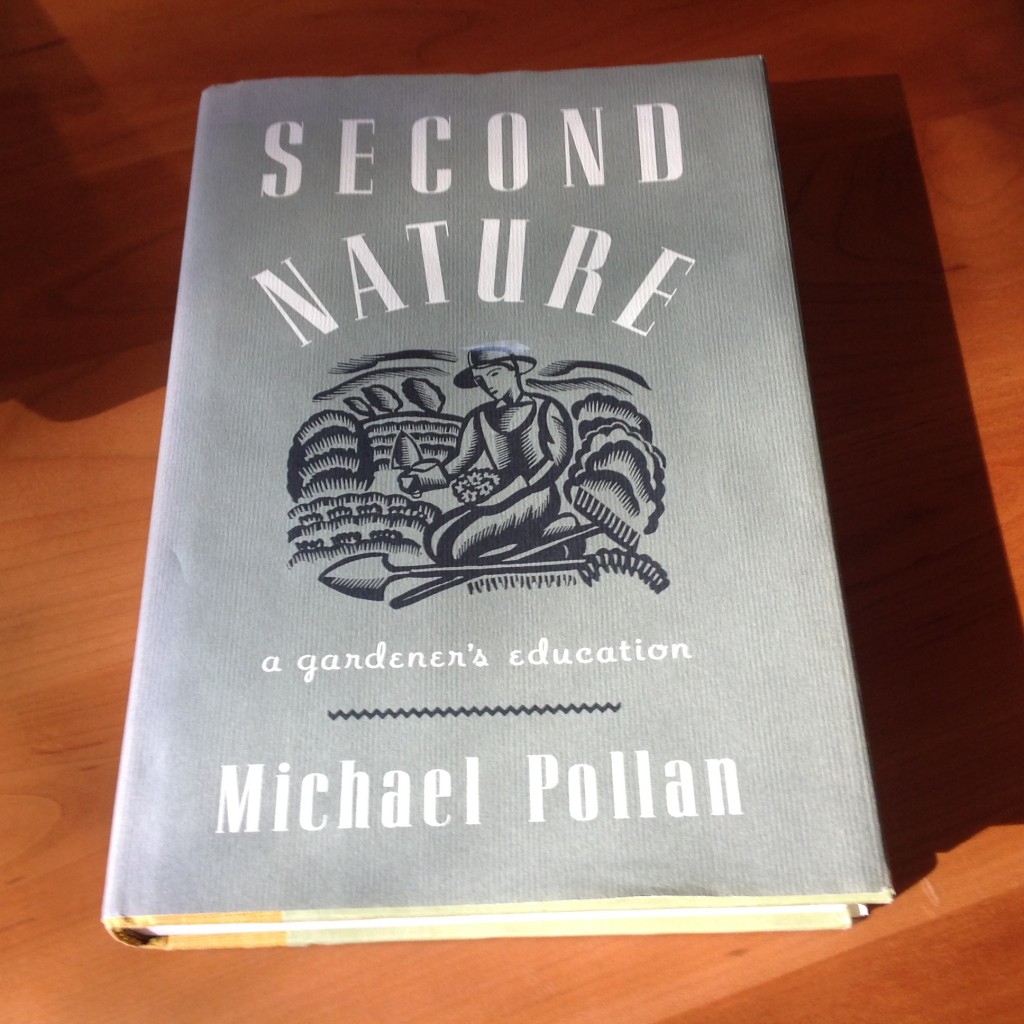

Just so yesterday, and I put aside the novel whose words are still novel to me and began to root in a bookcase. I needed something to read that I could read. For 7th time I pulled out Michael Pollan’s Second Nature, a book bought long enough ago to have endured some fading of its cover. Gardening, I thought; why not? Perhaps promise of green would distract me from the austere white that had fallen overnight and seemed to blanket my mind.

Pollan’s book began quietly, but early on there was small, contentious mention of Thoreau. He would, said Pollan wrangle some with America’s prophet of the wild; he would, it seemed, stake out some middle ground where a garden grows, and already the lines of argument seemed clear. Also, I was hooked. Out of my wooliness and into Pollan’s world.

It helped that his sentences were clear and clean, and it helped too that he began with little stories of his childhood and its first exposures to gardens and growings via familial tension between an imperious gardening grandfather and Pollan’s indoor-oriented, weed-tolerant father.

And then Pollan’s contentions with Thoreau offered me a few of my own with Pollan – more reason to read on; the book was now burred to me.

Perhaps you too talk back to books you like. Here’s one little conversation from yesterday:

Pollan: Thoreau is gardening here, of course, and this forces him at least for a time to throw out his romanticism about nature — to drop what naturalists today hail as his precocious “biocentrism” (as opposed to anthropocentrism. But by the end of the chapter, his bean field having achieved its purpose, Thoreau trudges back — lamely, it seems to me — to the Emersonian fold: ‘The sun looks on our cultivated fields and on the prairies and forests without distinction…Do not these beans grow for woodchucks too?…How then can our harvest fail? Shall I not rejoice also at the abundance of the weeds whose seeds are the granary of the birds?’

Surely, Henry, rejoice. And starve.

me: Ah, Michael…At the outset, Henry describes his time and work at Walden as an “experiment”; no less the bean field. And the purpose of that experiment is expansive, is to press understanding outside the narrow rows of his time’s dominant industry, agriculture. Henry’s bean field chapter is, in part, celebration that he will not have to tie himself to a life of beans and starve his mind, that sun can shine on him “without distinction” as well.

I have, of course, done to Pollan what he has done to Thoreau, plunked him down without full context to contend a point. But isn’t that the real fun of finding yourself drawn into a book’s lines, where you find yourself mumbling occasional objection and reaching for a pencil to scribble both retort and praise?

And, most important, I will read on.