By Corinne H. Smith

How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book. ~ Thoreau, “Reading,” Walden

Five years ago, 31-year-old Matt Steel of St. Louis read Thoreau’s Walden for the first time. Or at least, he tried to read it. He found the going a bit rough. First of all, he was accessing a copy of the unformatted text on his iPad, which didn’t make the words visually appealing. His reading sessions were interrupted at whim whenever text messages or software updates chimed through the device. (The irony of using a tool designed for multitasking in order to read a book encouraging simplicity was not lost on him, either.) And then there was the matter of Thoreau’s use of 19th-century language and references to classical literature. Now, Matt is a smart guy, and he really wanted to read Walden. At this time in his life, he felt he NEEDED to read it. But barriers kept appearing.

Finally, between the iPad screen and a 1993 Barnes & Noble print copy of Walden (loaned to him by his mother), Matt got deeper into the book. And he was blown away. He connected with Thoreau’s ideas immediately and found similarities in his own life – with an interest in closeness to nature, the independence and rights of the individual, the choice to live deliberately. Most of all he admired the concept of simplicity “and intentional slowness, leaving room for higher, transformative pursuits,” as he calls it. The concepts resonated with this busy, married, father of three who searched for a balance of work, rest, and play in his own life. He saw Thoreau as a benevolent teacher who was willing to share his ideas with an eager new student.

Matt became an instant Walden fan. And he wanted to pass along his enthusiasm for the book with everyone he met. But as many of us Thoreauvians have discovered, he found he had to couch his recommendations. This situation bothered him. “I didn’t want to have to always provide a caveat,” he said. “I didn’t want to keep telling people they should read Walden – ‘BUT’ …”

We know this “but.” But: the first chapter, “Economy,” is long and can be difficult to manage. But: sometimes you have to read long sentences a few times to fully understand them. But: Thoreau seems to follow tangents on occasion, and he refers to pieces of classical literature that few readers are familiar with today. But, but, but.

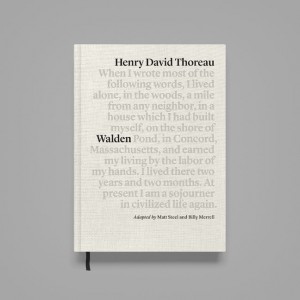

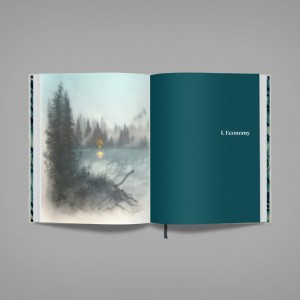

As a lover of language and as an accomplished graphic designer, Matt thought he could come up with a solution for these challenges. He could produce a better looking book with good typography, layout, and illustrations, first of all. He also could update syntax and find better ways of conveying those older cultural references to contemporary readers. In essence, he could create a version of Walden as if Thoreau were writing it in the 21st-century. The project soon became larger than he first anticipated. He backtracked and did some research on Thoreau’s life, including devouring Walter Harding’s biography, The Days of Henry Thoreau. And he added two new members to his team to help him: co-editor writer and poet Billy Merrell, who is also a Thoreau fan; and illustrator Brooks Salzwedel, who specializes in scenes of nature and the environment.

Matt was inspired by the recent example set by book designer Adam Lewis Greene. In 2014, Greene announced his goal to redesign and rework the language and structure of the Bible. He created a linguistic update of a public-domain translation of the text. He launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise $37,000 to cover his publication costs – and met this goal in just 24 hours. To date, Greene has gotten $1.4 million in pledged funds for his new version of the Bible. The four-volume Bibliotheca is currently in production and is available for pre-order. If the Bible could be adapted and updated, Matt thought, why not Walden?

Matt has spent the last eight months working with the text. He is quick to point out that he is not “simplifying” or dumbing it down. He’s not removing any of Thoreau’s ideas from the original book. He did break up “Economy” into multiple thematic chapters for easier understanding, however. And he’s not imposing his own style of writing onto Thoreau’s work. He’s scrutinizing each line and determining whether or not it may require translation into contemporary American speech.

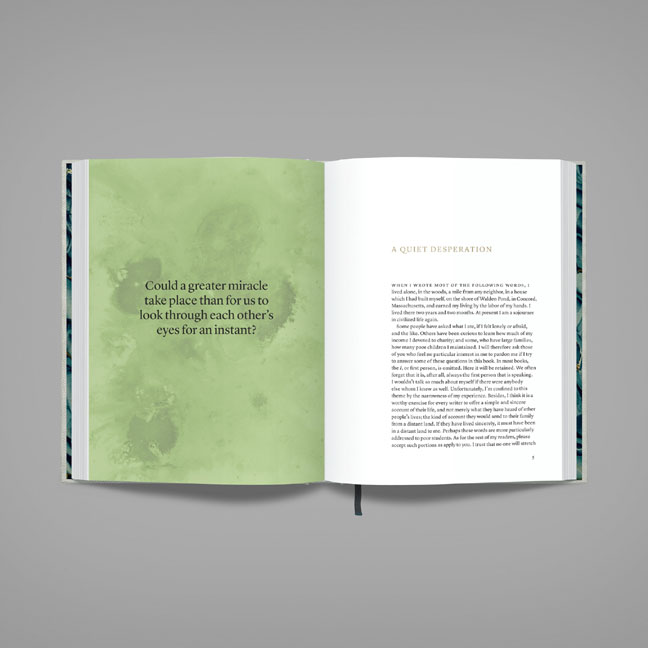

For example: take one of Thoreau’s best-known sentences: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

In order to replace the old-time use of the gender specific, Matt at first altered the line to: “Most people lead lives of quiet desperation.”

Upon further reflection, he knew these words didn’t carry quite the same meaning as the original. Now he is leaning instead toward: “The masses lead lives of quiet desperation.”

And he’s still not sure. We’ll have to wait to find out what the final decision will be.

Matt has learned much since he took on this personal project. He says that his respect for Henry Thoreau and for the man’s most famous book have escalated over the past months. He is humbled by the complexity he finds in Thoreau’s poetic prose. He believes that Thoreau’s retreat to the pond and his public sharing of the experience through publishing the book in 1854 was “a great act of philanthropy.” “If Thoreau had been the hermit some folks still assume he was,” Matt says, “he could have kept his ideas and his words to himself. This wasn’t the case. I believe he was a teacher at heart, until the day he died.”

And yet, he knows how committed Thoreau fans are to the original Walden. Some folks consider it their own Bible. Matt assures us that the new book doesn’t seek to replace the original. He hopes people will look at both versions side by side and will give his edition a chance. Or, perhaps, that Thoreauvians may point to his book as a new reader’s way into Walden’s world. You can see a preview of the first chapters at https://medium.com/life-learning/walden-part-1-economy-chapter-1-d0c7eb6e35d#.69h7gwozh.

To fund this project, Matt Steel will launch his own Kickstarter campaign on February 16, 2016. He intends to print 2,000 copies of his Walden adaptation later this year. When it comes out, Matt will be 37: the same age that Thoreau was at the time of his publication in 1854. This story is yet another example of the influence Henry Thoreau continues to have on individuals today. We wish him good luck!