It is clear that I have never been here before – this early winter, 1860 section of my 1906 edition of the journals is rife with uncut pages; drawing a knife carefully along the joined edge of two pages is a little like opening a present or finding a secret glade. I have never seen these words, these observations, before; and yet each is a little window into a world I’ve come to know, to anticipate.

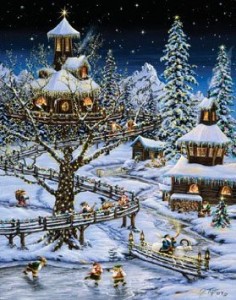

Like many children who grew itchy at time’s slow passage as Christmas neared, I liked the advent calendar. December’s dark days seemed a sort of tunneling toward magic, and the calendar’s little windows lit the way. My more religious grandmother had given the calendar to her somewhat-wayward son’s family, and in one season I had memorized each window’s offering. Still, until each window opened and its little painting appeared, the future felt like mystery.

Now, as I reopen each in memory, I realize that they were refreshingly free of religious iconography, that most of the tiny paintings behind the doors showed birds, pine cones, trees and snow; our calendar was paean to the world beyond the windows, and, during the short days of waiting for first snow and the 25th’s presents, that’s where I went to pass the time.

That you could only open one advent window per day kept time tugging at its reins. The fifth, as I recall, featured a Christmas tree, and sometime during that week, we too got our tree, which then spent the obligatory 48 hours in a bucket of sugar-water outside the backdoor. The candles along our mantle mimicked the green and yellow painting of day eight. Double figures neared, then arrived.

Now, I no longer have an advent calendar, but the habit of countdown remains; I imagine little woodland scenes behind the door to each day; then I go looking for them. And in this season of small windows, I confess that I have been bad, a little. Each day, when I’ve picked up Thoreau’s journal, I have opened more than one page, read more than one window’s words. That turns out to have been unavoidable, because after December 4th, Thoreau recorded little of that December.

The largest door in my remembered advent calendar was, of course, that of the 25th; behind it lay the day toward which we had been counting. The 25th doesn’t appear in Thoreau’s 1860 journal, but the 26th bears mention of what must have been a present received on the 25th. That year Thoreau’s 25th opened to an owl: “Melvin sent to me yesterday a perfect Strix asio, or red owl of Wilson, — not at all gray.”

And, in the next paragraph, Thoreau’s fascination with the details of his gift are clear. As ever, the windows of Henry Thoreau’s calendar opened to the natural world, even when it was brought to him as a present. And this gift-owl was part of a local habit wherein Thoreau’s neighbors brought to him their findings from the woods when it opened its windows to them.

In my long ago calendar, we too had an owl; it was painted into one of the early December days, its large eyes looking out in anticipation. I didn’t know then these little paintings of the owl and the fir tree and the snowy path led to the present I’d receive over a lifetime. But perhaps, when she selected that woodland calendar, my grandmother intuited it.