The knife I use to open the still-joined pages in my edition of Thoreau’s journal comes from Durango, Colorado; more precisely, it comes from a trail that winds above the town into the mountains. There, one morning as we walked up, finding our way eventually to a 12,000’ high point, I noticed anomaly packed into the reddish dirt; a flat, black stone, I thought. As I bent to look, I saw patterning, which resolved as the incised side of a 5-inch buck-knife. I dug it out, looked instinctively around for the owner, and, seeing no one, pocketed my find. No one else had been there for weeks.

That evening, I cleaned the knife, washing away the grit, scrubbing the blade, which soon shone dully, even as it held a fine edge. It became my trail-knife, both in the hills, and along the long reach of Thoreau’s uncut journals. If I look closely, I can still see the red dirt from that long-ago trail lining the cross-hatchings on the knife’s side.

Over time, I’ve come across a few other incisions as I’ve dropped like some small, literary paratrooper into this journal or that. A few whole pages have been sliced from this 1906 edition, and, of course, that has made me curious. The writer from whom I received these books struck me – though I knew her only a little – as a preserver. She had been a local newspaper editor and historian, and, when people wanted an answer to a town question from the past, they were likely to hear, “Go ask Eleanor. She’ll know.”

Each week, Eleanor would write a column about some local evolution, and each week, my wife, who edited the paper, would stop by to collect that column. Eleanor seemed to lead an interior life at that time, and most often the column, typed with the old Courier font, would be in a basket in the entryway to her house. Still, some connection must have formed, because one spring, books in boxes began to accompany the columns. And one of those boxes – two actually – held the 1906 edition on Thoreau’s journal and published works.

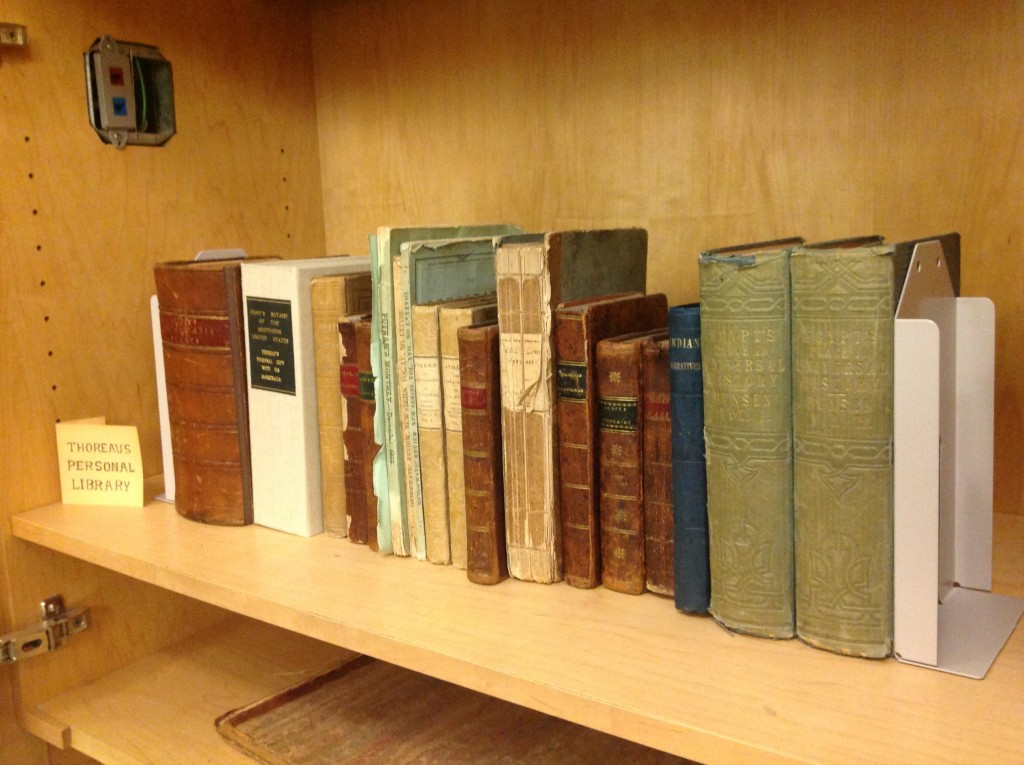

Some of the books that contributed to Thoreau’s journals. Henry’s Walden Pond library, as on display in the Special Collections at the Middlebury College Library.

Some years passed before I noticed the first missing page; its cut was straight and clean. It had been careful work. I had, by that time, devised my own cutting ritual, using my found buck-knife for the joined pages in sections Eleanor and whoever had owned these books before hadn’t opened. If I took care and drew the blade steadily toward me and down the seam, the paper parted so each page matched. If I hurried or even turned my head a little toward distraction, the paper would tear into ragged edges, though most of the time the generous margins left the writing intact. Still, each poor cut felt like injury.

But this excised page puzzled, and I looked into it. Research brought a few fantastic moments: might I have, as gift, one of the 600 Manuscript Editions, the 1906 printing that bound in a page of Thoreau’s original journal to each 20 volume set? I sat back in a little dream of discovery’s edge.

Well, no. Those editions were numbered; mine was not. A quick search on line shows that copies of the Manuscript Edition are still out there for sale…if you have roughly $20,000 to spare. My edition, the Walden Edition, clearly issued from a usual print run, part of a broader stream of publication, and a pencil notation suggested that Eleanor had acquired it in 1987, for the meager sum of $25. What then had been cut cleanly out? I would have to find out when I next met this set of books in some other library.

Still, this gift edition carries forward, offering affirmation and surprise. And, as further reward, during my sleuthing, I’ve reread Emerson’s unadorned and adoring introductory pages, his eulogy for Thoreau; its simple sentences pointed simply, admiringly, to genius in the pages ahead. To someone a cut above.

Link to Atlantic Monthly archive of the original publication of Emerson’s eulogy in 1862: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1862/08/thoreau/306418/