In Search of Bedrock at Walden

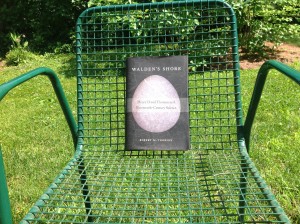

Part of summer’s joy lies in its liberal stretches of reading time. And so the gift of a book often offers immediate rather than delayed pleasure. The other day I received such a gift: Robert Thorson’s Walden’s Shore is a detailed examination of Thoreau and 19th-century geo-science. Thorson is a geology professor at University of Connecticut, and he brings an earth scientist’s deep knowledge of what we walk upon to the work of watching and walking with Henry Thoreau throughout his lifetime.

Noted Thoreau scholar, Jeffrey Cramer, offers a book blurb saying, “Walden’s Shore has no predecessor in the field of Thoreau studies. It is a welcome addition and needed reassessment of an iconic figure.” I’ve found this true. Part of the difficulty of reading Thoreau lies in his transcendence of time – he speaks across ages with insights that lift him from the context of his own time, and a reader can end up looking up to him in a way that leaves that reader ungrounded. There is irony in this of course, because Thoreau’s vision is rooted in his ability to stay very much on the ground, to see in fact into it and take the measure of whatever moves on and through his days in Concord.

Thorson’s gift is also to see beyond the immediate and into what’s often called “deep time” and the shaping of the world we walk. We learn how the surface features at and around Walden tell stories remarkably similar to those intuited by Thoreau during his intense examination of those features. And, from Thorson’s particular reading of Thoreau’s journals, we see a tracery of Thoreau’s deepening tendency toward scientific measurement and thinking as he writes Walden. Thorson keeps track of “every entry where Thoreau seemed to be mensurating or thinking spatially beyond what would have been expected of a competent naturalist of his day.” Before 11/23/50, Thorson finds no cases; from that date forward to the close of the Walden period on 4/27/54,” Thorson counts 62 cases. This reading makes a nice summary of Thoreau’s evolving scientific mind.

“Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe…till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality,” Thoreau writes in Walden. And Thorson then endeavors to show his readers just where that bedrock bottom is and how Thoreau, ever prescient, apprehended it, well before modern sensing and imaging devices confirmed many of his views.

Thorson also sums up scientific thinking before and up to Thoreau’s writing of Walden, and limns Thoreau’s place in the scientific ferment of his day, when that era’s creationists first felt the swelling power of Darwin’s theories. This is useful, necessary context for a deeper appreciation of Thoreau’s work and intelligence. But, if that were all Walden’s Shore offered I would have stalled in mid book.

For me, a reader (and sometimes writer) of stories, Walden’s Shore’s gifts and appeal are deepened by the interlacing of imagined narratives throughout the book. Just when geologic theory threatens to deaden or swamp my mind, Thorson cuts to narrative – there, then, is Thoreau out walking and recording and opining about what he sees. Here then is the living character in real time, and the drift of continents and clash of tectonics becomes – as it is in our lives – backdrop for our fascination with people.

As Thorson writes in his introduction, “This book is heavily biased toward presenting Thoreau as a competent, pioneering geoscientist. With few exceptions, I emphasize what he got right and overlook what he got wrong or didn’t notice. Mine is not a fair and balanced treatment.” Yes…and because this is at root a narrative of human exploration that seems just fine.

Added note: Thorson writes with clear sentences and an understanding of narrative’s lures and power. That may sound like usual praise; it is not.