Surveying the Tommy Wheeler farm.

Again, as so many times, I am reminded of the advantage to the poet, and philosopher, and naturalist, and whomsoever, of pursuing from time to time some other business than his chosen one, — seeing with the side of the eye. The poet will so get visions which no deliberate abandonment can secure. The philosopher is so forced to recognize principles which long study might not detect. And the naturalist even will stumble upon some new and unexpected flower or animal. Thoreau, Journal, 4/28/56

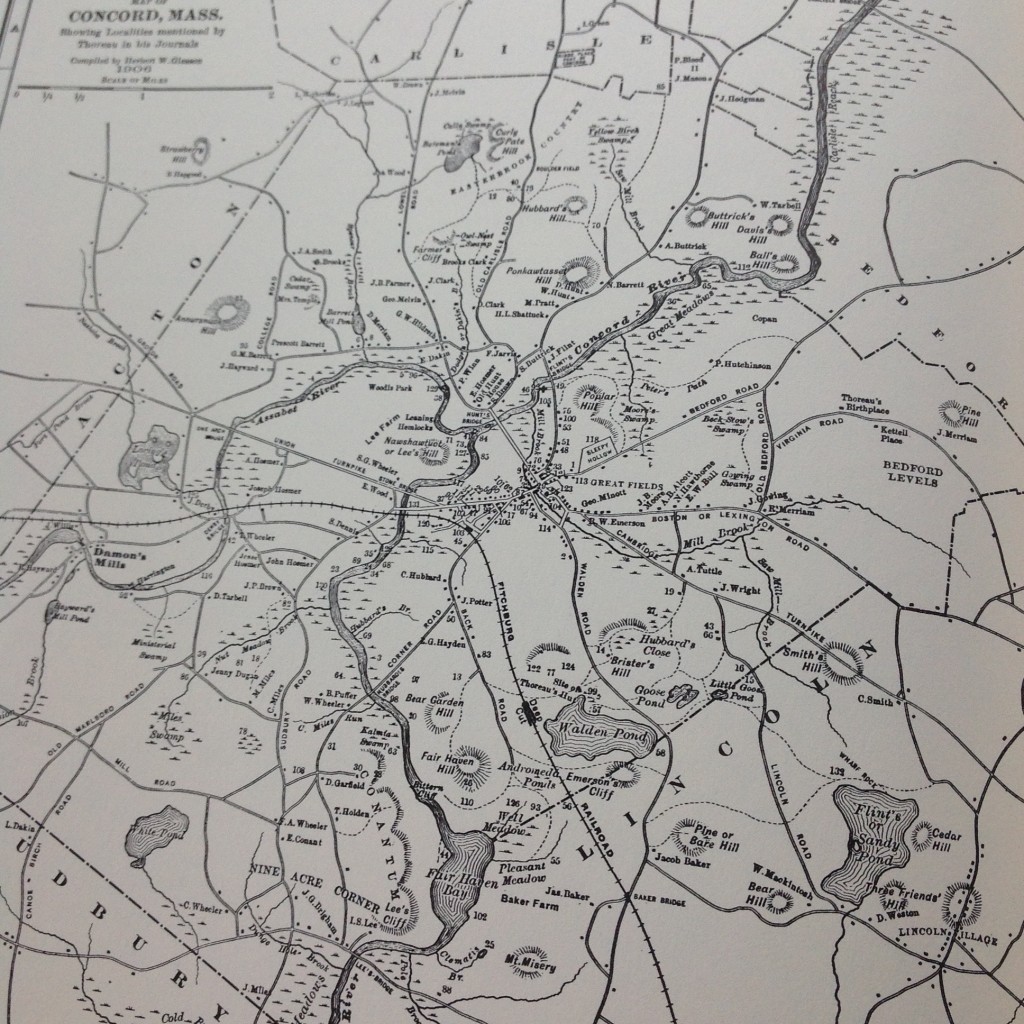

Henry Thoreau had no real fondness for surveying, even as he had a talent for it, and it provided him with steady work (when he wanted it) and some of his family’s income. Still he profited not only from the work, but also from its habits of foot-found measurement. Not only could Thoreau pace off land and boundaries with formidable accuracy, but he also grew used to and adept at seeing maps on the ground. And though this habit fostered too a sort of ambivalence, his mapping eye was a sort of “seeing with the side of the eye,” I think, and the maps he formed of the Concord area grew well beyond the making of boundaries for which he was paid. They became illustrated, animated, narrative maps as well, and his stories flowed from them.

Thoreau’s mappings and mapping-mind came to mind recently as I read an essay by Kim Tingley about the Secrets of the Wave Pilots of the Marshall Islands in the NY Times Magazine. Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/20/magazine/the-secrets-of-the-wave-pilots.html?_r=0

Some scientists had traveled to these Pacific Islands to see if they could understand the navigations of wave pilots, who, for hundreds of years, had sailed over seemingly trackless seas from island to island. The best wave pilots navigated with remarkable accuracy and without instruments; reportedly, they did so by sensing variations in the waves that showed them what they called the di lep, the way on the water.

The article was long and the years of summarized science complex, but it turned on a sort of cognitive mapping, which the wave pilots learned, and which yielded familiar water and known routes from what everyone else sees as chaos. In particular these wave pilots had grown adept at reading the way waves interacted with the widespread islands, setting up distinctive patterns that suggested where those islands were over the horizon. And the idea of sensitivity to surroundings shaping maps in the mind called up similar, land-based experiences that I’ve had in familiar hills I’ve walked for tens of years.

Just as one of the story’s wave pilots could orient himself by reading and feeling immediate waves, I’ve found that, even in the fog of cloud banks, and even in the absence of trails, certain trees and rocks and slopes suggest the way. There is, however, a qualifying IF: such orientation works if I carry in my mind an overall map of the area, and that map is a composite of study and experience. The study comes from my habit of reading topo-maps (or sea charts) for fun; the experience comes from being a foot pilot in the terrain of those maps. Over time, across land, it becomes a familiarity that I follow, even in “trackless woods.” My familiarity may not take me over miles to visit a particular tree, as Henry Thoreau sometimes did, but I can see how the miles of walking and re-walking have formed mind-maps. And how, sometimes in those woods, I feel “everywhere at home.”

And that offers a whiff of understanding for how wave pilots may develop their exquisite readings of water.

And for another time: The essay also speculates about a fascinating link between motion over sea and land and our narrative inclinations and abilities – in short, it wonders if our stories come from our memories of motion. Thoreau, I think, would lean (or walk) in that direction. He would read Tingley’s narrative of the di lep avidly.