By Sandy Stott

It seems a bit counterintuitive that, as the hours of daylight stretch out toward solstice and invite us outside, many of us also become expansive in our reading. But early summer brims with experiment; sleep seems distant kin of the other solstice. We sing the day elastic.

And so there seems also ample time for that sweetest of slow times, summer reading. Here is a briefly annotated list of summer books that also might have interested Henry, though, given his omnivorous reading appetite, that would be a safe wager in many instances.

This House of Sky – Ivan Doig: a lyrical first book by a noted writer of western landscapes (and behaviors), this memoir about Scottish immigrants making their way in another hard land is one of my favorites.

Reading the Mountains of Home – John Elder: Take Robert Frost’s great poem, “Directive,” topo maps of the mountains outside of Bristol, Vermont, Middlebury English professor, John Elder and ample stretches of time and combine them and you get a superb meditation on what it is to be guided into knowing a home landscape, which finally yields knowing home.

Teaching a Stone to Talk – Annie Dillard: Yes, this book of essays has knocked around for years, but it is still in print for good reason. Written after Dillard’s homage to Henry, A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, these sometimes cryptic pieces were Dillard’s primary work. Some of the essays – Total Eclipse, Living Like Weasels, Teaching a Stone to Talk – have been heavily anthologized.

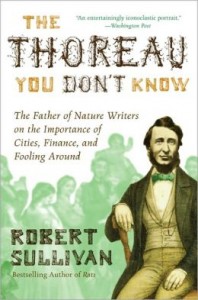

The Thoreau You Don’t Know – Robert Sullivan: Would Henry have picked up a book about himself? If he’d been introduced to Robert Sullivan’s earlier work, perhaps he would have. Sullivan is a quirky mind drawn to off-the-beaten-track subjects – see his books, Rats or The Meadowlands – and so his take on Thoreau avoids others’ tracks too. A very fine storyteller.

Seek – Denis Johnson: Join the essayist on his honeymoon in the Alaska bush, where he and his bride contract with a bush pilot notorious for coming down hard, aka, crashing. Finally, Johnson and wife are out there 100 miles from anyone to pan for gold so they can forge their own rings; the bush is not interested. What else do they learn? Other essays from the edges of our world, a number of them grim. One of the best stylists writing.

Street Haunting – Virginia Woolf’s classic essay about rambling the streets of London resonates – for me – with Thoreau’s daily footborne looks at his world, even as the settings are wildly different. Woolf’s writing makes more music than most writers can imagine.

And you, what are your summer reads? Send them on and we can compile a list loosely linked to Thoreau, who, after all, read globally.