His Hands Your Hands – Meeting Thoreau’s Copy of Walden

It is, to begin with, a plain, brown book; shifted from its climate-controlled home and away from its guardian curator, it wouldn’t draw your eye at a tag sale. But you pull on the white cloth gloves that are a size too small, and you reach forward to where the curator has nested the book on a protective, foam wedge; in doing so you reach over the years – at least that’s the feeling – and somehow the book still feels impossibly far away. From July 22, 2013 to August 2, 1854, which, according to his journal, is when Thoreau first lifted his ‘specimen” copy of his book and opened its plain cover.

You wonder: did he scrawl his name on the first page immediately, an odd redundancy since his name was already embossed on the book? And, whenever he did so, was it with one of his own pencils, the graphite riding smoothly over the paper? Surely, you think, of course, though a second glance shows that he chose ink – my copy, indelibly.

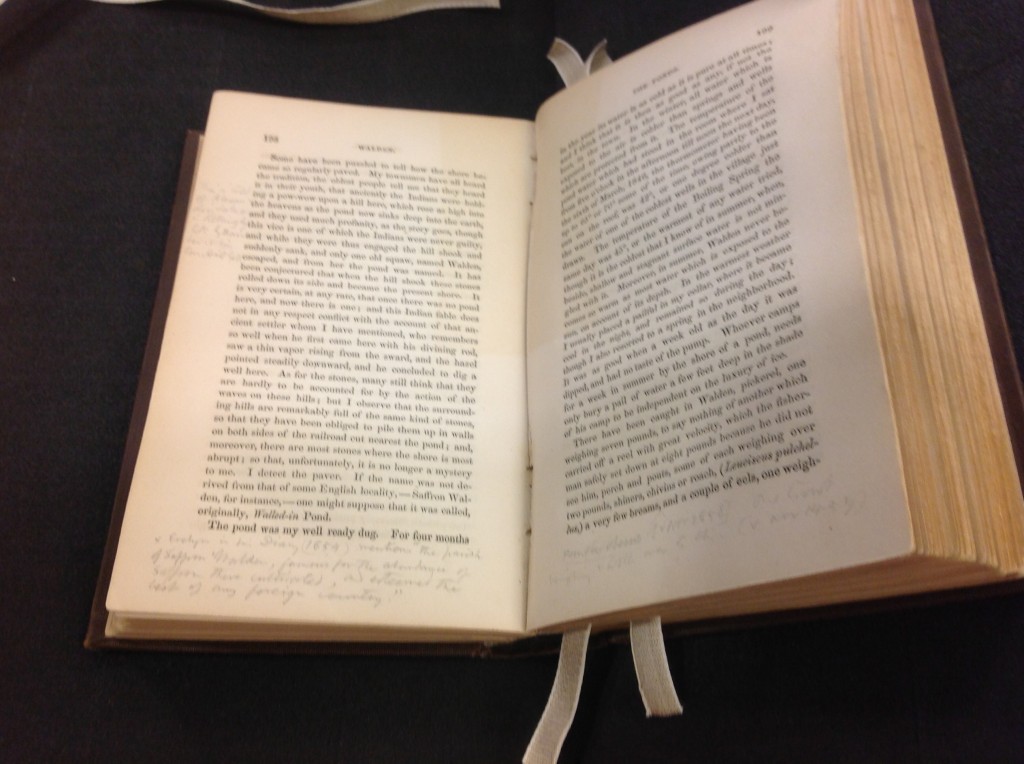

It is about the size of your own modern copy, and so you notice that the pagination isn’t far off – favorite passages are near the page numbers that are lodged in your mind from teaching and rereadings. What has drawn you, however, the first reason you reach across this span of years is that this copy contains his emendations -pencilled-in notes as he reread his pages and brought to bear what he knew now on what he knew then. Here is evidence of his passage among his own lines.

Your curator has thoughtfully printed out a list of the pages (only a handful) with emendations – it will save you both time and, more important, it will save wear on the book, which you learn at the end of your visit is Middlebury College’s second-most valuable holding (which explains also why you are never left alone with it, and why it goes back into a vault with shiny locks as soon as you are done). Purchased in 1940 for $2000, its value now outpaces numbers.

Not many notes, you think, as your hand rests on your own heavily-scribed copy. But then, his book is the distillation of so many notes, while your copy is record of how he has expanded your thoughts, of the way they have furled out from it.

Your curator has also marked the three lengthiest comments, each with a lace that allows you to draw open the book to that page without having to search for it. The fantasy is that you will discover a hidden key, some little authorial confession that unlocks part of the text, but there is no such baring of hidden purpose. Well that makes sense, you think: his book is a baring of purpose; why would he obscure its meaning?

A long note at the bottom of a page in The Ponds chapter noses deeper into the naming of Walden Pond, specifically into the possibility that it is derived from Saffron Walden. You squint at the famously difficult scrawl and find the note clearer than the copies of manuscript pages you have tried to decipher in the past. But then, you think, this is a note, a detail, and not the broad and wild course of his mind, which he must have had to hurry his writing to ride, its current whirling, leaping, hurrying as he bent to his journal’s or manuscript’s page. And so, beside the clear pool of this finished writing, there is this quiet note that speaks also of the writer’s precision, his drive (even after nine drafts) to get each detail right.

And then you go the ending, read its final paragraphs – “The sun is but a morning star.” – and you are cast out of Walden (as he intended, you think) and into the world of your eyes and imagination. You close the plain, brown volume, reach with your gloved hands and heft it for a moment. Its weight is precisely what he felt when he lifted it to consider what he had made of his world.

Note of Thanks: to Danielle Rougeau, Assistant Curator of Special Collections & Archives/Exhibits Designer at the Middlebury College Library.