“I have great faith in a seed. Convince me that you have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.” Henry Thoreau

Sisyphus at Solstice

Well that was, as always, a long way down to where the year’s slope relaxes and my stone is still.

But here’s a day of rest at the bottom; then, I get to begin the work I like, pushing this glowing rock uphill, seeing it add to each day a thumbnail’s worth of light on both margins. From here to the stretched light of summer’s a long climb. But that climb begins right after 11:49 p.m. on the 21st.; we top out next year on June 20th.

It’s not that I mind going downhill into this dark nick in time. Every day’s a gift, and I’ve said often that November’s long sightlines make it my favorite month. But like all my breathing brethren, I like also the light that rims each growing day, and I like the easy warmth it suggests may come.

Mostly, however, as I imagine my part in rolling this light up toward the sky, I like the direction – uphill is all about life; climbing is living. And so being put to this stony task seems also the greatest gift imaginable. Who wouldn’t go gladly, day in, day out, to this work?

What is funny, I reflect while testing shoulder to stone, rocking it a little, is that the old gods thought they’d devised the perfect torment when they set me this work. They thought it all added up to nothing. But they, in their haste, gave me a stone that’s round and weighted nicely to my strength. And they gave me – bless them, foremost – a hill to climb. And then, as if those gifts weren’t enough, I got also two days of pause, this near one down here at bottom, the other in the high country of summer light. Solstices.

And I get to do this forever.

Second Solstice Story

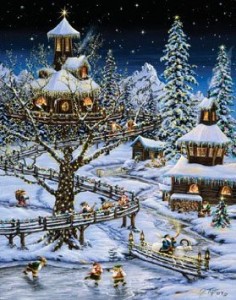

The other evening, as a rare (for this year) cold front blew in, we went to a solstice party. Even as we took the narrowing roads that went finally to dirt, the lid of darkness slipped over the land; strings of lights stirred and winked in the wind. The house was warm and food-filled, and the small percussions of exclamation and laughter added to that warmth. We burn words too against darkness.

Later in the evening everyone bundled on coats and trundled back outside…for a celebration of light. A fire burned in an outdoor chiminea, but the wind quickly snuffed the candles and lanterns we carried; a few headlamps flashed on. We listened to the sweet voice of a child as he joined his mother in singing a nursery school song about light. Then, we held copies of a Wendell Berry piece aloft to catch the headlamp light and read together about an enduring sycamore he knows. Our murmur of voices threaded the wind.

Our eyes turned then toward the yard, where our host prepared an unsanctioned evocation of light that he promised would bring “slightly longer days starting soon. Just watch,” he said.

We looked up, as if from the bottom of a long well; the half-moon slipped behind a flying cloud; it was gone. Then, in rapid succession – green, red, blue, gold, gold again – little orbs of light raced up into the sky, where they blew into bright cinders that arced slowly back our way. The Roman Candles gave way then to the fizzing rise of three streaks against the night’s slate, and, above our upturned faces, each opened with a soft pop into starburst. Again, again, again.

Evocation of light drifted over the dark pines and settled down, seeding our minds.