By Kristi L. Martin

American society is currently embroiled in a political tumult over the suitability of certain public monuments and what to do with those that are questionably objectionable to present sensibilities and values. This raises abstract questions about the values of American society, as well as the symbolic meaning and power invested in objects. These questions interest me as an American public historian.

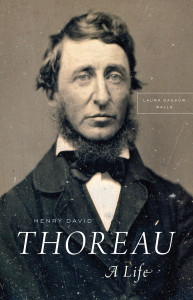

Yet, thoughtful conversations seem hard to come by in this moment of impassioned civil strife, cultural disconnect, and often violent agitation. Ours is a moment in history that resonates with the writings and life of Henry Thoreau on many levels. Hailed as the forefather of “civil disobedience” and spokesman for living a life of principle, Thoreau was an ardent abolitionist who had little use for the form of politics. Thoreau was also an advocate of listening intently.

Amid the angry, echo chamber of voices on social media, I stopped scrolling on a post that was distinctly different in tone from all the others – serenely composed, without sacrificing the strength of the author’s principles. I read:

“I would have no problem living my life without statues of specific people. Give me more trees, flowers, open skies, waving grasses, freely flying birds, roaming herds of animals and all of God’s creation. If man feels that isn’t enough, make your artwork general. No human being is that important we need to see them immortalized in stone.”

I was struck by the uniqueness of this statement. Here was someone not arguing for memorializing this human over that human. Instead the author appealed to the transcendent humility of human history in the grandeur scheme of the life. Her words reached something in my heart that elevated my thoughts above the turmoil and disquiet. I was instantly reminded of Thoreau.

On September 18, 1859, Thoreau recorded in his journal that he was asked to contribute toward a statue in memory of his neighbor, the educational reformer Horace Mann.

Thoreau wrote, “I declined, and said that I thought man ought not any more to take up room in the world after he was dead. We shall lose one advantage of a man’s dying if we are to have a statue of him forthwith. This is probably meant to be an opposition statue to [Daniel] Webster. At this rate they will crowd the streets with them. A man will have to add a clause to his will. ‘No statue to be made of me.’ It is very offensive to my imagination to see the dying stiffening into statues at this rate. We should wait till their bones begin to crumble – and then avoid too near a likeness to the living.”

Thoreau died in 1862, three years before the end of the Civil War. I will not condescend to imagine what Thoreau might say about our present day debates regarding monuments. Though it begs the question of what Thoreau would think of the statue of himself that now stands near Walden Pond.

The proliferation of public monuments to statements that Thoreau lamented were part of nation building in the 19th century. New Englanders attempted to define their own historical heroes in granite and thereby what cultural values would be upheld in the future.

The passage from Thoreau resonates more deeply with present debates than its general comment on public statuary. Daniel Webster was a noted statesman and famed orator, who disgraced his reputation in the estimation of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau by enforcing the Fugitive Slave Law, requiring New Englanders to comply with slavery. Horace Mann, whose statue Thoreau presumed was to be erected opposite of Webster’s on Boston Common, literally opposed Webster over the Fugitive Slave Law in Congress. But this is more of an aside, than to the purpose.

What I’d like to draw out of this passage in connection to the social media post written by my friend Lisa, is not a debate or an answer to a debate. My purpose is to draw out the quality of reflection, humility, and transcendence present in both passages in response to the impulse conceit, and predictability of reaction.

Rather than prompt further debate, controversy, or angst, reading Lisa’s words took me outside of myself, outside of anger, worry, and fear. Her words inspired me to surrender my own ego, to let go of the loud opinions bombarding my virtual environment, and to reconnect to the nurturing beauty of nature and my higher self. Perhaps you, too, will want to decline relation to stone statues – at least for a moment. Perhaps you, too, will go outside and look up at the sky, smell the air, feel the wind, listen to the birds, taste the fruits of the season, and remember the blessing of being human … and be present, be peace, for a Thoreauvian moment.

Kristi Martin is a doctoral candidate in the American and New England Studies, Boston University and is a historical interpreter at Thoreau Farm.