Their gray stalks stand still at attention. Even after winter’s varied batterings, many of them are intact, though closer inspection finds the ground littered with remnants too. On this sunny, early March morning when winter seems to have given up on itself, the southwest breeze brings scent of ocean, and it stirs also these milkweeds. As I watch, a finger of air finds one brown seed suspended beneath its silky white parachute, and the whole ensemble lifts off; at eye-level, it sways in place, seems to hesitate, then it flies upfield, with the wind.

All across this small forest-girt meadow, this flight happens again and again, and sometimes the air seems seeded with a snow that rises, that aims to ascend again to the sky. I am mesmerized by the flight of seeds. Also by their promise.

I let one go, and it rises slowly and uncertainly at first, now driven this way, then that, by invisible currents, and I fear it will make shipwreck against the neighboring wood. But no; as it approaches it, it surely rise above it, and then feeling the strong north wind, it is borne off rapidly in the opposite direction, over Deacon Farrar’s woods, ever rising higher and higher, and tossing and heaved about with every fluctuation of the air, till at fifty rods off and one hundred feet above the earth, steering south — I lose sight of it. Thoreau, Faith in a Seed

When I left for home, I took with me two pods, one with its silky seed-strands matted by winter snow and water, the other seemingly just burst. Along the way a few seeds floated away – I was, intentionally for a while, one of Nature’s dispersers. I was also drawn by the colors of the pods, a driftwood-pale-gray, against which the white seed strands glowed, and the dark brown heart of seed suspended below. A perfect composite of earth and sky.

Thoreau observed milkweed seeds closely, and, of course, counted them too, finding 134 in one pod and 270 in another.

Despite its weedy surname, milkweed is no throwaway plant. Not, anyway, if you like the monarch butterfly. Preferred food and nursing-station for the larvae of these remarkable migrant butterflies, milkweeds have long been under human attack for their seeming uselessness. They are no “crop,” goes the reasoning, so why cede field-space to them?

But if your crop is beauty and miracle, if, in short, your crop is life, then you will admire the milkweed. Not only do its seeds fly finely on the wind, but they enable also the multinational life of the monarch. Reason enough to praise rather than poison the milkweed.

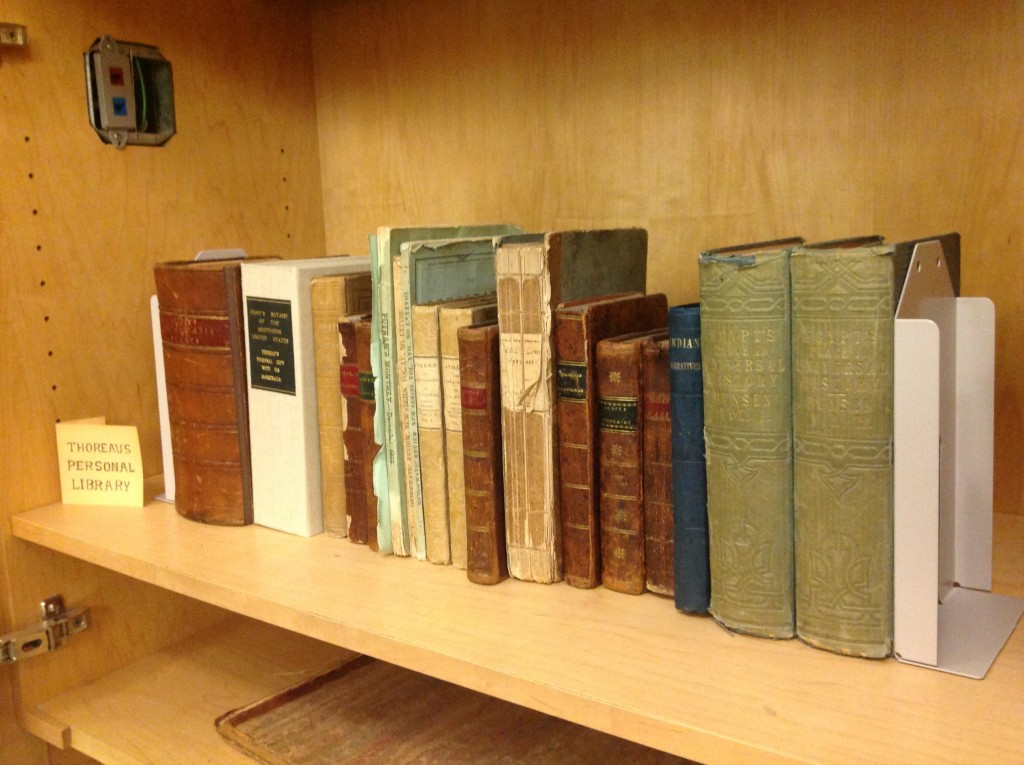

And as often happens with sightings while I walk, these milkweeds have sent me back to readings, both on line and in Faith in a Seed, Brad Dean’s remarkable “first publication of Thoreau’s last manuscript” in 1993. It is the finest kind of spring reading.

Here’s an excellent University of Minnesota website for Monarch Questions: http://monarchlab.org/biology-and-research/ask-the-expert/faq/