by Natasha Shabat

For the past 16 months, I’ve been video-interviewing visitors to Walden Pond. Approaching random strangers at the pond requires going out of my comfort zone. Normally I photograph nature at the pond and post my photos on Facebook — on my own page, on the Thoreau Society group page, on other Concord-related pages — and print them on greeting cards. And, with the encouragement of some Thoreauvian friends, I created a Facebook blog called “Walden Pond People” and turned my camera toward people, talking with them about why they were visiting the pond.

Come summer of 2016 and the Annual Gathering of the Thoreau Society (AG16), I invited attendees to meet me at Walden Pond, Monday morning after the Gathering, to be interviewed at Thoreau’s Cove. I chose this rendezvous point since it’s easy to find, and it’s quieter near the western end of the pond.

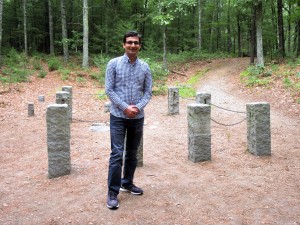

Meanwhile, thanks to my Walden Pond photos on the Thoreau Society Facebook group, I had befriended Punit, a man from India, who had been in the U.S. for less than two years and was starting to explore the country.

“Walden Pond is one of my dream places to visit,” Punit told me last April.

In July, Punit traveled to New England to attend AG16. He had never been to Boston, Concord, or Walden Pond and attended AG presentations over the weekend, including mine on “Walden Pond People.” He waited to make his pilgrimage to the pond for when we met at Thoreau’s Cove for his “Walden Pond People” interview.

“I wanted to read more about philosophy. I picked up Gandhi, because of the impact he made on the destiny of India, the future of India, so I wanted to know more about him. When I read his autobiography there was something on ‘Civil Disobedience,’ which I later came to know was inspired by Thoreau’s essay. Another reason why I was attracted to Thoreau’s writings is because one of my friends recommended Walden to me. There were a lot of things which were telling me ‘Hey, go read Thoreau!’ So, first I got my book. I just bought it and put it on the shelf. I didn’t do anything with it!”

When Punit described his path toward Thoreau, he reminded me of my own experience. I, too, had bought a copy of Walden, put it on the shelf, and proceeded to not read it. I simply continued going to Walden Pond to swim, kayak and read and write, as I’d already been doing for a couple of decades.

Punit continued, “But my friends influenced me. They started reading Walden before I did. Then there were three of us reading this book at the same time. There are certain things in the book which are difficult to understand. So what we would do is, we would discuss these with each other through email, or by phone, or during the in-person meetings. Yeah, it was a fun way to read a book. I’ve never done anything like that with any other book. It was a really interesting way to study these ideas. ‘What does this guy even want to say in these lines?’”

As Punit, I was influenced by others finally to take my book off the shelf. In my case it was a bunch of Thoreauvians presenting at AG11, which I had spontaneously attended. There at the Masonic Temple in Concord I was surrounded by people who knew Walden and had plenty to say about it. I was intrigued enough finally to read Walden for my first time. I read it in small bites, chewing on Thoreau’s words, while sitting in my kayak on Walden Pond. I did this over the next six weeks, until I turned the last page on September 1, 2011.

“How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book.” — Walden, “Reading”

Punit: “I think of Walden, and Thoreau’s writing in general, I think of them as something which is connecting the dots. Think of civilizations which existed in a different time. On a scale of time. Think of Chinese civilization, Indian, or Hindu civilizations, or American, or European civilization. So Thoreau’s trying to connect the dots. As if he were saying ‘Hey! There really isn’t much difference between these different civilizations. The core philosophy remains the same.’”

After I finished reading Walden that summer of 2011, I, too, observed some dot-connecting, but of another sort: I was overcome by the parallels between Thoreau’s masterpiece and the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes. (More on this another time.)

Punit: “That core philosophy is one of the reasons that Thoreau got inspired by Eastern philosophy, even though he lived so much later afterward. That’s just amazing for me! And since I’m from India, Hindu philosophy especially attracted me to Walden. I think it’s really important to figure out what you want to do in life. This is one of those books which actually helped me to figure that out.

“Walden Pond is exactly what I was thinking of, how I imagined it to be: a simple place, just trees, pond, that’s it. It’s very peaceful, very nice, very green. Just the kind of place you want to be in when you want to think about the higher purpose of life, bigger things in life. Well, the cabin actually looks smaller than what I thought, so I’m wondering how Thoreau lived in such a small cabin. I would find it difficult. . . . he was here for a grander purpose, so it probably suited his purposes here.

“I really like the site of his cabin. I think he probably must have walked around the pond a lot of times. Probably there is some specific reason why he chose this as his site. I brought my camera – that’s really important, because I wanted to capture at least a part of what Thoreau felt. And I would love to visit this place again.”

I was impressed with Punit. Imagine living in India, learning about Thoreau as a result of studying Gandhi — and then, eventually, actually coming here to Concord, hoping to see what Thoreau saw and feel what Thoreau felt. Punit had graciously awarded me the privilege of accompanying him on his first-ever pilgrimage to the place where Thoreau wrote Walden. I felt honored.