by Debbie Bier

Do you know where your food has been the last 10,000 years?

I don’t mean where it was grown or how it traveled to your plate – which are worthy questions, certainly – but its history over the course of centuries or millennia. In what part of the world did it originate? Was it bred for specific characteristics? How were its genetics preserved to grow and end up on your plate today? This is something I ponder often as I tend the kitchen garden at Thoreau Farm – in fact, it’s become a favorite moving meditation over the years.

All this garden’s plant varieties were carefully chosen, known or reasonably assumed to have been in New England by 1878. That’s the year the house was moved to its current location, and the date we therefore chose for our exterior restoration. Mostly, the roughly 70 varieties we are growing this year go back much further than 1878. Some decades earlier, others centuries… some even stretch far back into human prehistory. As we take this photographic tour around the mid-summer 2014 kitchen garden, I’d like to point out some of these plants and their history. I hope next time you shop, garden, prepare, or sit down to eat a meal, you’ll find yourself curious about the larger history of what you’re eating. And since this goes back to the miracle of the seed, “…be prepared to expect wonders!”

The Early Purple Vienna Kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea) I’m clutching in the photo here is a pre-1860 variety grown for its tender, delicious, swollen, bulb-like stem and copious, beautiful leaves. There is also a green Vienna available from the same era, but I think: why grow a green plant when a purple one is available? Kohlrabi is an unusual looking plant that evokes silliness among our visitors – which is why everyone is laughing in the photo.

The Egyptian Walking Onion (Allium proliferum) is one of our most marveled-at plants by visitors. This unusual 1850s variety is not Egyptian in the least – but it sure does walk! These are perennial scallions that reproduce by setting a top cluster of bulbils, which look exactly like tiny red onions. The weight of the developing cluster causes its up-to-4’-long stalk to fall over and touch the ground. At that point, the bulbils put down roots and sprout leaves. You can see the cluster in my hand here is already sprouting to the tune of 6” long leaves! They are amazingly hardy and come up early in the spring, quickly supplying us with copious quantities of scallions right up until winter’s heavy snow covers them. Visitors often use the word “alien” to describe it.

An 1845 corn variety first grown in Virginia, Bloody Butcher (Zea mays), has distinctive, long root-like structures that are sent down from the first and sometimes second nodes along its stalk. Feel free to refer to them as we do: corn toes. It was bred by crossing Native American corn with the European settlers’ seed. At Thoreau Farm, we grow it for grinding, though it was a favorite “moonshine” corn in its day. This corn is deep maroon when mature, hence the “blood” in its name. It grinds up purple and is a dark gray-blue when baked into cornbread.

We grow more than one dark red plant that uses “blood” in its name, another being the 1840’s Bull’s Blood beet (Beta vulgaris) with its intensely dark red-purple (almost chocolate brown) leaves. More typically grown for its foliage for use in salad mixes, it does have a lovely small beet that reveals white rings running through the crimson when it’s cut. It was so long popular for its leaves that rumor had it that the bulb was inedible – which is nonsense. I love to plant the various beet varieties clustered together, the Bull’s Blood here mixing with the 1820s Golden Beet, and the pre-1811 Early Wonder Top Beet. This year it’s also flanked by an improved version of the 1871 Danver’s Carrot developed in nearby Danvers, MA.

Have you ever wondered exactly where the poppy seeds on your bagel come from? In this photo, we see poppy seeds growing in two stages: a future potential in the open flower of the Breadseed Poppy (Papaver somniferum), and to its left, the still-ripening pod where the seeds are forming. This plant was bred to have none of the natural openings in the pod so the seed wouldn’t be spilled before harvest. That’s some pretty smart and successful breeding!

We grow the Cherokee Trail of Tears Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) to honor the Cherokee who carried this bean over the Trail of Tears, the infamous winter death march from the Smoky Mountains to Oklahoma (1838-1839) that left 4,000 dead along the way. I chose this bean to connect us to Thoreau’s deep sense of social justice and interest in the native peoples here. The pods are tender and succulent as string beans, though we grow them mostly for their gorgeous shiny black dried beans. Visit the house in early September, and you’ll see the pods will have swollen and turned a dusky purple on their way to full maturity. When cooked, the dried beans are rich and flavorful in ways our typical canned black beans never could be. Heirloom beans are amazingly delicious – that they have rabid devotees is understandable once you taste them. Down with canned, flavorless beans!

When it comes to certain squash and pumpkins, we have to look back millennia to view their history. The “flying saucer” patty pan and the ever-abundant yellow crooknecks (both Curcurbita pepo) are believed to have pre-historic North American origins. Our white patty pan – “White Custard Squash” – was documented in Spain in 1591, where it arrived from the New World. In 1722, it was documented growing in what is now the United States, planted by Colonial settlers.

The pure breeding of squash varieties – which is what makes the characteristics of the parents breed true in their offspring – over millennia boggles my mind. Truth be told: squash of the same species (though different varieties) will cross-pollinate willy-nilly in the garden. To properly save seed, both male and female squash blossoms must to be isolated and then hand-pollinated. (In this photo, the fading pumpkin flowers across the bottom are males with their thin, long stems; the flower hanging downwards at the top is a female with an ovary behind the dying flower that looks just like a miniature pumpkin.) To maintain these varieties for hundreds or thousands of years takes real devotion, and endless generations of hands doing the job correctly, faithfully year after year after year. Thinking about squash varieties that are thousands of years old, I am both astonished and grateful to those long-gone farmers.

In contrast, all of the commercial seed stock from the wonderful delicate squash was ruined a few years ago by improper pollination methods. If it were not for home seed savers who held pure seed and were able to restore it to commercial production, we would no longer have this lovely variety – it would have been lost forever.

Between the super-powered, nutrient-dense goat manure from small local goat herds, and the fantastic seed, much of which we save ourselves and are adapting to perform best in this location, the garden this year is absolutely fantastic! Do visit any time, particularly weekends 11a-4p until October, when you can also tour the inside of the house.

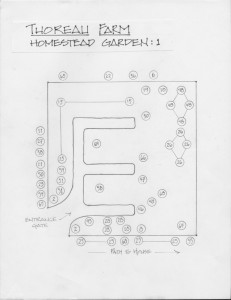

The 2014 Thoreau Farm Kitchen Garden map and the 2014 Thoreau Farm Kitchen Garden planting list are included at the end of this post; they may be copied for reference.

Deborah Bier is a Thoreau Farm Board member. She created and has manages our Kitchen Garden. She is also on the steering committee of the Concord Seed Lending Library, for which Thoreau Farm grows seed and educates the public. www.ConcordSeedLendingLibrary.com