By Corinne H. Smith

It’s a misty and golden autumn morning. I use the windshield wipers once or twice as I set out to drive to Concord. At least there’s no icy film on the glass. And the grass in the yards is glistening with just dew, not white frost. A freeze is fast approaching, though. You can feel it in the air.

I head to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery first. I haven’t checked in with the 19th-century folks in a while. At this hour, even on a Saturday, I may have the place to myself. I can stand in front of the little marker that says HENRY as long as I want to. I can bring him up to date with whatever I feel like telling him, without being interrupted. Tomorrow I’ll be back here in tour guide mode, with a large group of people surrounding me. I won’t have the opportunity then to catch a private moment.

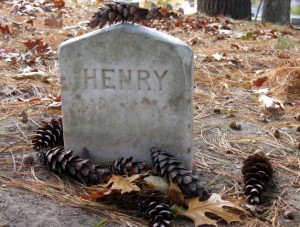

I pick up a pinecone on my walk up the hill. You can’t visit Henry Thoreau empty-handed and without bringing him a present from Nature. When I reach the Thoreau family plot, I’m shocked to see only a single nut (either butternut or beech) lying in front of his marker. The gravesites have been cleaned. I look around. No one else – not the Hawthornes, Louisa May Alcott, or even the great Mr. Emerson himself – has any gifts lying on or near his/her stone. I place the pinecone in front of HENRY and look around for something else. I find a sprig of tiny acorns that the squirrels and chipmunks have missed. I add it to the patch of raw earth in front of the granite. Then I step back to breathe and absorb the atmosphere.

This glacial ridge is among the most peaceful places in Concord. On this October day, the oaks and maples and pines decorate the edges of the scene with yellows and reds and greens. Squirrels and chipmunks busy themselves in the leaf litter. One squirrel is perched on a nearby branch, barking a warning to his colleagues. “I’m not a threat,” I tell him. “I’m not after you or your food supply.” Somehow, he doesn’t believe me. A gathering of Canada geese honk from behind me, down in the wetland called Cat Pond. A pair of crows – or are they ravens? – silently take off from one tall tree and land at the top of another, across the way. I shiver with a fleeting thought of Edgar Allan Poe. But he’s not here. He’s down in Baltimore.

By the time Kristi Martin took this photo on the following Tuesday, many more pine cones had found their way to HENRY.

When I look at the HENRY stone again, my eyes are drawn to its top right-hand corner. The rock-face is a little whiter here, sustaining more wear than from just the action of mere age and weather alone. Someone felt the need to take home more than just a photo. Someone wanted a piece of Henry David Thoreau; and since this wasn’t possible, he/she carved off a slice of his headstone instead. Perhaps the thief (or thieves) were unaware that this isn’t the original 1862 stone. Heck, it may not even be the first replacement for the original stone.

Most of the members of the Thoreau family were first interred down the hill in the New Burying Ground. Today, this plot is as close as you can get to the intersection of Bedford Road and Monument Street and still be on cemetery land. The Dunbars lie there still, beside an empty space. The Thoreaus were moved up to Author’s Ridge in the 1870s. The current large family THOREAU stone was put into place in 1890, when it was donated by Benjamin B. Thatcher of Bangor, Maine. His mother was Henry Thoreau’s cousin, Rebecca Billings Thatcher.

As for the individual name markers, I’m not sure of their vintage. However, the story goes that someone visited this ridge one day and was shocked to find that the HENRY stone was missing. (While I can’t locate documentation to confirm the details at the moment, this probably happened during the late 1960s or early 1970s. The jail site marker was stolen at least twice in the same time period.)

Presumably, the stone had been stolen. Arrangements were quickly made to get a replacement installed with as little fanfare as possible. As a result, the one we see today has been standing there only for a handful of decades. A friend now tells me that the HENRY stone may not even sit in the right place within the family plot. Egad! How can anything so simple become so complex?

In the end, this marker – like the ones at Walden Pond, and elsewhere – is merely a symbol for something much larger. We look at it, and we think. We leave little mementos behind in silent tribute. We feel satisfaction when we do this.

I leave Sleepy Hollow believing that there’s enough of Henry David Thoreau’s legacy for every one of us to share. We need not be greedy. We need not take slices of stone to make an intimate connection. But if you ever see an old granite HENRY stone offered at a yard sale, please let me know.