By Scott Berkley

“Each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest of five hundred or a thousand acres, where a stick should never be cut for fuel, a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation. … If any owners of these tracts are about the leave the world without natural heirs who need or deserve to be specially remembered, they will do wisely to abandon their possession to all, and not will them to some individual who perhaps has enough already.” — Henry David Thoreau, Journal. October 15, 1859

On the late-summer day last year when the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument was announced, former Roost editor Sandy Stott was out paddling a kayak in the Gulf of Maine. When he returned to the news that the state of Maine had added a parcel of the immense North Woods to its stock of public lands, the connection to Henry Thoreau, who loved both the northern reaches of New England and the idea of land deeded to the public good rather than held by private interests, was immediately evident. To Thoreau, the purpose of setting aside public lands was to make them “a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation,” as he put it in his journal.

When I met up with Sandy in Maine later in the fall, we went land-ward to the Brunswick Commons, a parcel set squarely between the housing developments which ring that prosperous coastal town and the manicured playing fields of Bowdoin College. The Brunswick town Commons – which have made an appearance on The Roost in the past – are encircled by all the signs of a community becoming more and more of a paved metropolis. And yet the sandy trails meandering across marshlands dense with low sedge and scraggly pitch pines seemed, as I ran through the slanting autumn light, to exist as the beating heart of the town as a whole – a region that spoke back to the encroaching development. Let every town have its forest, says Thoreau; and let it be, by extension, not separate from the town, but at the basis of this larger ecological and spatial community.

This past month, I found myself thinking often of Thoreau’s public-lands dictum and what it tells us about land use in the twenty-first century. In the past four weeks travel took me to two of our nation’s most famed national parks: Yellowstone and Great Smokies. On the move in these hallowed places of wild land, I thought about the historical importance of these National Parks, this one-hundred-and-one year-old idea. Even more, I thought about how the millions of acres in the national park system speak to the tiny parcels of public lands in towns like Brunswick, and how the town-parks speak back to these iconic locales that take up so much space in our collective American consciousness.

On my way to Yellowstone, I found one such town-park in the city of Bozeman, at the south end of the Bridger Mountains of Montana. Over the past few years a local nonprofit, the Gallatin Valley Land Trust, has spearheaded an ambitious trail-building initiative known as “Main Street to the Mountains,” connecting urban bike paths and trails in places like Linley Park and Peet’s Hill to mountain trails leading to the Bridger Ridge. As of next year, when a new connector trail is finished, a trail runner or hiker will be able to go from downtown to Mt. Baldy at the south end of the Bridgers without having to find a way to drive to the trailhead.

A new bridge on the Drinking Horse Mountain trail, near Bozeman, MT.

Photo from gallatinartcrossing.com

Two weeks later, in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, I recalled the significance of Bozeman’s urban trails when I visited Le Conte Lodge, perched near the summit of the park’s second-highest mountain. The continued existence of the Lodge, where up to sixty overnight guests can stay during the March-through-October full-service season, testified to the eleven million visitors who come to the Smokies each year. Le Conte itself is a kind of town, even in the cold and foggy month of March; dozens of dayhikers came to visit the Lodge, even though it was closed for the winter, every day. Bozeman’s trail network creates a park experience even in the midst of urban development, while Le Conte Lodge recalls how humans can interact with expansive wild places on their own terms: by finding a way to make a home in the mountains.

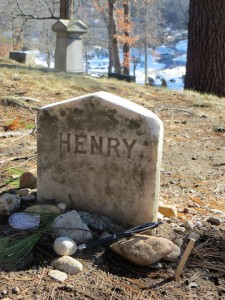

Back in my hometown of Concord after the second leg of this two-park tour, it was again the familiar, lower-case parks that beckoned: Walden Woods; Fairyland, with its stone engravings of quotes from Thoreau and Emerson; Estabrook Woods, where those two once walked. One quote not engraved was Thoreau’s advice to wealthy landowners, to “abandon” their holdings “to all, and not will them to some individual who perhaps has enough already.” Fascinating word, abandon – as though the common, once given over to the shareholders of a town or country, were a place to be left alone rather than used and appreciated for generations. One hopes that, in this time of increasing socioeconomic inequality and political volatility, the town common is true to its name, binding us together in the shared joy of use.

Scott Berkley, a recent graduate of Middlebury College, has worked for the past five years in the huts of the White Mountains and is at home at all speeds on woodland trails.