By Lawrence Millman

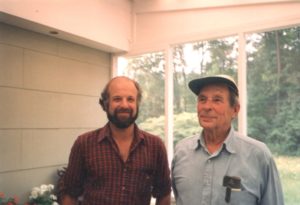

Elliott Merrick died in 1997 less than three weeks before his 92nd birthday. Toward the end of his life, he would joke that he was so old he’d become “historical.” But I didn’t think of him as historical at all. Rather, I thought he was an ardent contemporary. I also thought of him as a dear friend and mentor.

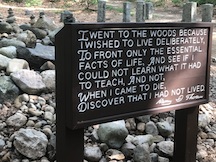

From the very beginning, Bud (as he was known to his friends) looked to Thoreau for guidance. For, like Henry, he believed that we should let Nature govern us rather than visa versa. He grew up in upscale Montclair, Jersey, and was educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale. After he graduated from the latter, he went to work for his father’s firm, the National Lead Company. But how could a young man for whom Walden was a veritable Bible devote his heart and soul to producing copy for Dutch Boy Paints?

The answer is a single word: Labrador. Bud signed on as a summer Worker Without Pay with Labrador’s Grenfell Mission. He fell in love with Labrador (“that pristine, beautiful land,” he called it) and stayed on as a schoolteacher in Northwest River. He also fell in love with the Mission’s resident nurse, the tough-minded Kate Austen, with whom he shared a palpable love of the out-of-doors and whom he sometimes referred to as “Cast-Iron Kate, the Boiler-Maker’s mate.” They were married in 1930, and for a time lived in a small cabin near where the Goose Bay Airport now stands.

The highlight of Bud’s Labrador years was a long winter trip he and Kate took with trapper John Michelin. From North West River, they journeyed by canoe and portage up the Grand (now the Churchill) River with Michelin and then continued by snowshoe and toboggan deep and deeper into the bush. Altogether, they covered more than 300 miles of mostly unexplored wilderness. The trip’s difficulties, for Bud, were not difficulties at all. In his journal, he wrote, “We have traveled to the earth’s core and found meaning.”

The Merricks returned to the United States in the early 1930s. “The day I left Labrador was the saddest day of my life,” Bud told me, adding, “A major in English from Yale hardly prepared me for a trapper’s life.” Eventually, they bought an old farm in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, one of the few parts of the country that could ever be mistaken for boreal Labrador. Indeed, the similarity of northern Vermont to Labrador doubtless gave Bud the distance he needed to write about the latter.

The book he wrote about his trip with John Michelin is a Walden of the North, its voice now celebrating the boreal wilderness, now decrying the urban one. Entitled True North, it starts out with a lengthy quote from Walden. From then on, the book (published in 1933) abounds with remarks that Henry himself might have made. “I prefer mud to cement, and water out of a bucket to water out of a faucet,” Bud says at the book’s beginning. “Do I want to bend my life to a system of law evolved solely to enable millions of people to live together packed like sardines in a tin?” he also says. To me, True North’s ecological message is more relevant today than it would have been when the book was published.

Bud later wrote an account of his life in northern Vermont entitled Green Mountain Farm. This is not a book that will teach you how to become a successful farmer, for success was not a word that’s part of Bud’s (or Henry’s) vocabulary. Indeed, Green Mountain Farm is not so much about renovating a hardscrabble farm as it is about renovating one’s soul by contact with the natural world. It concludes with this Thoreauvian utterance: “In me and in my children, I hope, will be a consciousness that natural things are as powerful and all-pervading as they were in the time of the pagan Greeks and the wine-dark sea and the sylvan gods.”

He continued writing about Labrador in his somewhat fictionalized autobiography Ever the Winds Blow (1936) and a novel about a traditional Labrador trapper entitled Frost and Fire, along with various magazine articles. Then, drawing on his wife Kate’s experiences as a nurse, he wrote Northern Nurse (1942), which is (in my humble opinion) the finest book ever written about a woman’s life in the North. (A personal note: I succeeded in getting Northern Nurse reprinted in 1994 and wrote an extended introduction for the reissue.)

Neither his writing nor the farm paid the bills, so Bud took a job as an instructor in English at the University of Vermont. The academic world was totally alien to his temperament. “Promise me that you’ll never become a professor,” he once told me in a grave voice, as if he were telling me not to become a serial killer. His dislike of professoring was genuine. Still, I can’t help but think that he might have liked it more if he could have done it in some open-air setting, in the middle of a lake, say, or on a mountain. As he wrote me in a letter: “Nature, love it or leave it, is all we’ve got.”

Bud was not only a staunch, but also a quite witty traditionalist. Here’s an example. I once wrote him about a pair of neoprene-and-aluminum snowshoes I’d used on a winter trip to Labrador. He wrote back: “I have invented a snowshoe far superior to your aluminum ones. Its frames are composed of old garden hose, which bends readily, taking either the bear paw shape or that of the Alaska tundra runner. Crossbars are of Victorian corset stays bound together with baling wire, and the mesh is of state-of-the-art chicken wire layered in an intricate pattern. I am depending on you as a qualified expert to see that my creation is installed in the Smithsonian’s Hall of Artifacts.”

I count myself fortunate to have been among the handful of people who were Bud’s wandering eyes and ears in his last years, when he was more or less housebound. If I encountered something unusual on a trip to Labrador or elsewhere in the North, I’d say to myself, “Wait until Bud hears about this!” And when I got home, I’d ring him up. He would query me closely about my experiences, and then maybe tell me that he knew the native camp I’d visited when it was still occupied some sixty years ago. Sometimes I’d hear the rustling of a map in the background.

Bud may or may not have been living vicariously through these conversations. One thing I do know, however: without him as an invisible sidekick, my own journeys in the North have become less interesting. Lonelier, too.

Lawrence Millman is an adventure travel writer and mycologist from Cambridge, Massachusetts.