By Lucille Stott

“Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.”

― Henry David Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience”

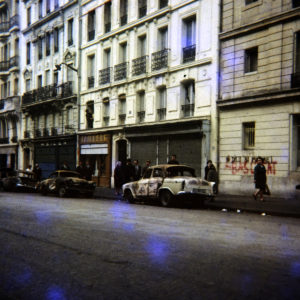

I stood on the balcony of the Roberts’ apartment overlooking the Boulevard de Strasbourg, watching students and riot police face off against each other. On this mild, sunny afternoon in mid-May, the scene felt surreal, like a bewildering moment in a Buñuel film. I don’t remember who charged first, but suddenly the two groups were on each other. Students hurled rocks, wielded tree branches, and yelled obscenities. Riot police fogged the air with tear gas and swung their nightsticks as they charged forward in a bloc.

I had my Kodak Instamatic camera in hand and started snapping photos. Two of the riot police knocked down a protester, and while one held him down, the other pummeled him again and again with his nightstick.

When I raised my camera again, I heard a cry from behind. My French mother, Madame Robert, was yelling for me to get back inside. I had never seen her so upset, and she had never once spoken to me in anger in the more than six months my roommate and I had been boarding with her family during our junior year in Paris. After getting me out of sight and back into her living room, Madame Robert started to cry. What if the riot police had spotted me? She was sure they would have stormed upstairs, smashed my camera, arrested me, and punished the Robert family.

Usually calm and reserved, Madame Robert had grown increasingly anxious as the street violence in Paris had escalated and the blare of sirens had become the soundtrack to our nights. After hauling me in from the balcony, she told me she had been suffering terrifying flashbacks to her childhood during the Nazi Occupation, when sirens had raged all night throughout the city, and she’d cowered in her parents’ bed. Her son was out there with the protesters, she reminded me, and even at home during the daylight hours, she didn’t feel safe.

For the first time since the student-led riots had begun in early May, I felt connected emotionally to what was happening around me. At 21, I was in Paris with the Hamilton College Junior Year Abroad program mainly to have fun and grab a bit of learning on the side. Most of our university classes had been suspended by then, and my American friends and I felt justified in not cracking our books. As we told each other repeatedly, history was being made in front of our eyes. The slogans scrawled on walls bore us out: “Power is in the streets!” “It’s forbidden to forbid!”

Youth uprisings like this one had been occurring in other countries — Mexico, Poland, West Germany, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Czechoslovakia, Brazil, even the Soviet Union — since early in 1968, and were to continue throughout the spring. The rebellion at Columbia University in the U.S., which had erupted in early April, had definitely grabbed our attention from afar. Yet of all the youth protests that occurred around the world during the first half of 1968, the Paris riots in May have become the most romanticized probably because, well, they happened in Paris. Immortalized in books and on film, the student uprising in the City of Light became lasting symbols of student disillusion and alienation.

For weeks, our tendency to treat the street riots as performance art had kept me immune from the dark side of these events. But witnessing the reality of the violence and seeing Madame Robert so shaken changed all that for me. I felt her fear and hated that what was happening in the street below was causing her to relive long-ago trauma. And I still have the Kodachrome reminders of what it looked and felt like to watch brutality up close and be powerless to do anything to stop it.

A big factor in the way I experienced those weeks was the fact that I wasn’t sharing my life on social media. I had no cell phone, no email, no Twitter, no Instagram, no Internet. There was no such thing as a 24-hour news cycle. It took five days for an airmailed letter to cross the Atlantic. International calls were hard to manage and very expensive. Out on the street, I was on my own. I couldn’t text a friend, my French family, or the director of our program with a question or concern. Today, the joke is, “If it’s not on Facebook, is it really happening?” It was really happening.

This month, France is marking the 50th anniversary of May ’68. When I think back on the passion that galvanized a small, but visible segment of my generation in France and at home, so many years ago, I do so with mixed feelings. On the one hand, I’m sad to have lost the wide-eyed, youthful exuberance that made optimism so natural and imagined positive change to be within reach. On the other hand, I took away from that month in Paris a lifelong aversion to extremism, no matter what side it professes to support. Back then, we over-estimated how much our generation could change the world, and the causes we fought for were undermined at times by the things I found so troubling in Paris: fanaticism, exploitation, self-interest, macho posturing. But the world did change after May ‘68—sometimes because of us, sometimes in spite of us. As someone who came of age in 1968 and is now merely “of age,” my years place me squarely with the old but my hope still rests with the young. What would be truly radical would be for us to bridge our generational divide and share what we have — melding knowledge with vision; experience with energy —and change the world together. Now that would be a revolution.

Lucille Stott is a charter board member emerita and former president of Thoreau Farm Trust. Check out the three entries on Lucille’s new blog, “Touchstone,” for a more in-depth look at the events of Paris ’68.