By Kristi Martin

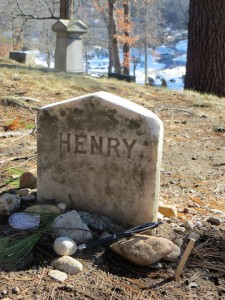

During the winter thaw, I went for a walk in Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. Henry David Thoreau’s grave is at the summit of a steep hilltop called “Author’s Ridge,” which is frequented by tourists making pilgrimages to the graves of Concord’s nineteenth-century literary residents. On this particular afternoon, I sought solace and inspiration on Sleepy Hollow’s paths. Various life circumstances and personal stresses had piled up over the winter months and I was feeling doubtful, unsure of how to handle the uncertainties of life.

Balmy temperatures rapidly melted the snow drifts accumulated from two recent storms. Small rivulets cut through the receding banks. The melt-water swirled into murky eddies and turbid, stagnant puddles, which I splashed through. In the warmth of  the sun, I removed my jacket and walked in my short sleeves. Closing my eyes, listening to the bird-song from the tree along the cemetery’s glacial ridges, I stood soaking in the warmth on my bare skin. Then the wind blew a distinctly cold breeze off the snow banks, dispelling the pleasant assurance of spring’s return; this was a false spring, a teasing spring; it was winter still. March is typically a changeable month with tumultuous fluctuations in weather. As the old adage assures, a mild beginning will in all probability turn tenaciously to snowy storms again before true spring flourishes.

the sun, I removed my jacket and walked in my short sleeves. Closing my eyes, listening to the bird-song from the tree along the cemetery’s glacial ridges, I stood soaking in the warmth on my bare skin. Then the wind blew a distinctly cold breeze off the snow banks, dispelling the pleasant assurance of spring’s return; this was a false spring, a teasing spring; it was winter still. March is typically a changeable month with tumultuous fluctuations in weather. As the old adage assures, a mild beginning will in all probability turn tenaciously to snowy storms again before true spring flourishes.

As I walked, the saturated ground had given way beneath my feet in places, but at Thoreau’s grave it was dry enough for me to sit on the bare earth. It is not unusual for this spot to be littered with mementoes left by visitors. However, at this time of year there were fewer. Among the rocks, pens, pencils, and pine twigs, I noticed a mollusk shell – a strikingly odd object to find in winter on a wooded New England hilltop. At once it mentally transported me to the nearby shores of Walden Pond, now nearly synonymous with Thoreau, and to the farther shores of Cape Cod, where he walked during three separate excursions.

For all the wit and wisdom distilled into his writings, Thoreau experienced misgivings and anxieties, too. In an 1841 poem he spoke of himself as a rootless and “dropping” flower bud seeking his life’s purpose.

He wrote, “I am a parcel of vain strivings tied…”[1]

In his journal the previous summer, he advised himself, “be grateful for every hour, and accept what it brings. …No day will have been wholly misspent, if one sincere, thoughtful page has been written. Let the daily tide leave some deposit on these pages, as it leaves sand and shells on the shore.”[2]

The shell on Thoreau’s grave reminded me that each day’s slow, but persistent accumulation amounts to something real, even if it seems but a grain of sand today.

“How vigilant we are! determined not to live by faith if we can avoid it; all the day long on the alert, at night we unwillingly say our prayers and commit ourselves to uncertainties. So thoroughly and sincerely are we compelled to live, reverencing our life, and denying the possibility of change. This is the only way, we say; but there are as many ways as there can be drawn radii from one centre. All change is a miracle to contemplate; but it is a miracle which is taking place every instant.”[3]

In that moment, as I sat looking at the shell in the cemetery, I heard in my mind: the price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it.[4]

For every anxious moment we exchange a moment of peace. We cannot control the swell of life around us – the deadline pressures, the frenzied societal expectations, those claims we put on ourselves to have already achieved something particular, fearful change, or even failures. We can, however, be grateful for the sand and shells, knowing many paths can be taken from here.

Kristi Martin is a doctoral candidate in the American and New England Studies, Boston University and is a historical interpreter at The Old Manse, the Ralph Waldo Emerson House, the Henry David Thoreau’s Birthplace, and Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House.

[1] Chapter One, “Economy.”

[2] This is a paraphrase; the actual Thoreau quotes is: “…the cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run,” Walden, “Economy.”

[3] “Sic Vita” was first published in the Transcendentalist journal the Dial in July 1841. It was later republished in A Week of the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849).

[4] Journal, July 6, 1840.

6 responses to “The price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it”