A recent conversation sent me, as many do, to consider what Henry Thoreau had to say on the matter. The trigger-question was about what separates art from life. Or, put differently, how does an artist integrate her or his art with life? Or vice versa? This is an age-old question, but also one that each generation bumps into. And it seems more pressing with the proliferation of art objects and us. What’s necessary, an artist may ask.

It seems to me that Henry Thoreau saw his life as his primary artistic expression – “to affect the quality of the day, that is the highest art.” Thoreau sought to be awake to and to affect the quality of each of his days. He deemed being so awake and aware the hardest of assignments.

Yesterday, while I was walking, I mulled the question further. It strikes me that a problem with art is captured by the word “representation.” Thoreau, for example, wrote to represent the experience and experimentation that he sought out every day during his Walden years. But when we pull apart the word, we get re…presentation, or presentation of something again. So, in a representation life is not art, it is instead an attempt to present some of that life again.

I think that Thoreau worked on this question near the end of Walden in his story about the artist from Kouroo. This artist sets out to make a staff – note, it’s not a representation of a staff, but the object itself. The artist’s goal is that the stick be perfect, and he is willing to spend whatever time necessary to achieve that perfection, because, as Thoreau writes, “Having considered that in an imperfect work time is an ingredient, but into a perfect work time does not enter, he said to himself, It shall be perfect in all respects, though I should do nothing else in my life.” p.326, (Princeton Edition)

As the artist sinks into his work, time disappears, dynasties fall, all of earth’s history passes by. I make of this that the markers – minutes, hours, years, etc. – of usual life vanish. And the artist enters a timeless act of creation. As he works, and whole eras and worlds go by, he concentrates on his staff; his whole life becomes the work.

When he finishes the staff, the artist looks up; everything is different. He is elsewhere. His staff is not a representation. It simply is, as is he.

So, perhaps when we create work in a way that means we “do nothing else in [our] li[ves],” the division between art and life disappears. We are present, as is our art.

There are also Thoreau’s thoughts about “volatile truth” at the top of page 325 in the Princeton Edition. Here’s he’s reflecting on the immediacy of creation and how its “residue,” the leftover language on the page, is inadequate to the moment it sought to capture. This again points to time’s passage as widening the gap between life (lived in the present) and art (re…presentation from the past).

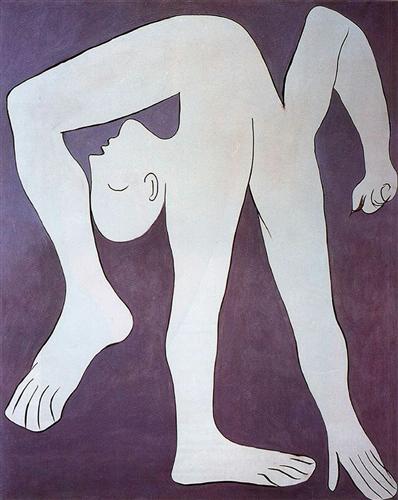

And, finally, here’s a short scene from a recent visit to the Picasso Museum. Perhaps, it’s just me, but I find myself distracted from the art on the walls by the people surging around me; they seem to mimic the art, to take on its characteristics, but in more compelling fashion. Life becomes what I watch; I get separated from it. The distinction between what’s on the wall and what’s around me blurs, the framing gets rearranged. Then, I come to my senses.

At the Picasso

At the reopened Picasso

Museum, bobbing amid the incoming

tide near the man with the out-

sized nose and the woman tipped

sideways by her chest and

every one is breaking up is

about to leave the frame

when I smell the orange and

turn – the woman next to me

peels it idly (like any breaker

of rules); the whole room

rushes back into place.